Some people think that the blues is something that is evil—I don’t. If the blues is delivered in the truth, which most of them are, if I sing the blues and tell the truth, what have I done? What have I committed? I haven’t lied.

Bluesman Henry Townsend1

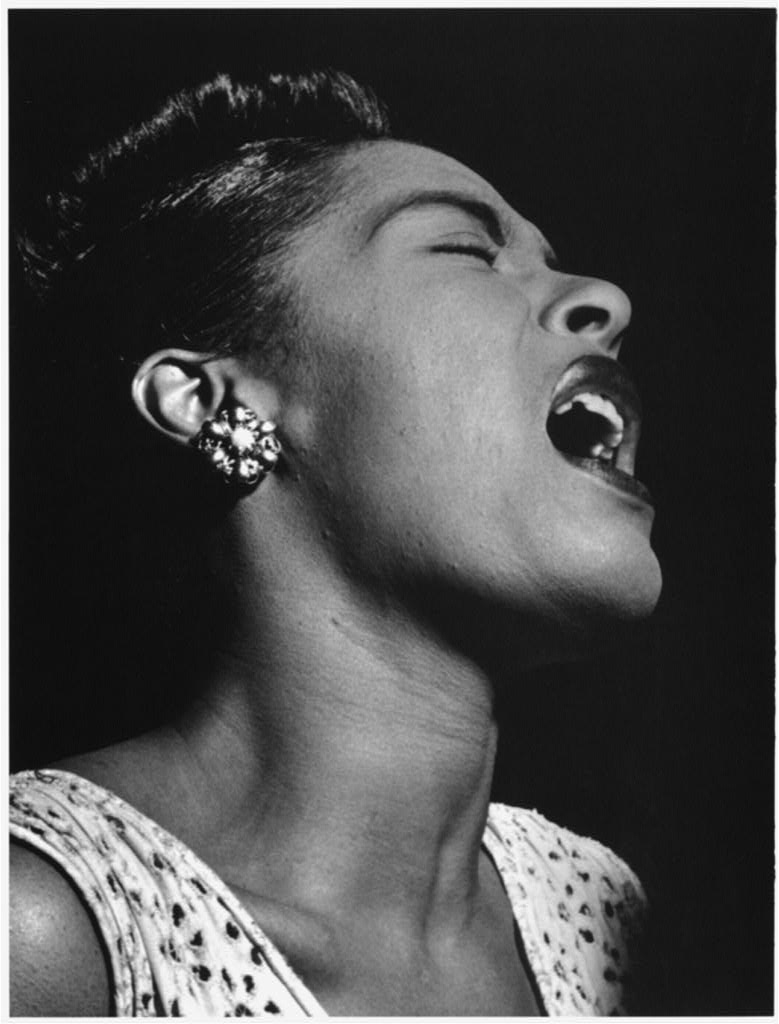

Late one evening in 1939, the patrons at the Manhattan nightclub knew something unusual was about to happen. Café Society, an unusually progressive club that welcomed white and black, performers and audiences, had a full house that night. The featured artist, Billie Holiday, had already at age twenty-four gained a reputation as a unique and moving interpreter of many popular songs such as “What a Little Moonlight Can Do.” But this night, before the final song of her set, the servers stopped serving, cigarettes were snuffed out, and the house lights were turned down save a single spotlight. The light illumined just her face, as if she were standing under a dim streetlight. The song began with Frankie Newton’s haunting muted trumpet crying out in repeated descending lines, giving way to Sonny White’s hushed, mournful piano. Half sitting on a stool, half standing, leaning into the microphone, Holiday slowly began her lament:

Southern trees bear a strange fruit

Blood on the leaves and blood at the root

Black bodies swinging in the Southern breeze

Strange fruit hanging from the poplar trees.

Not a glass clinked; not a muffled cough could be heard in the club. Slowly, with an artfully restrained tempo and emotion, she continued:

Pastoral scene of the gallant South

The bulging eyes and the twisted mouth

Scent of magnolia sweet and fresh

And the sudden smell of burning flesh.

Here is a fruit for the crows to pluck,

For the rain to gather, for the wind to suck,

For the sun to rot, for a tree to drop,

Here is a strange and bitter crop.

She brought the song to a beautiful, horrifying end holding a high note on “crop” as if imagining the hanging bodies in her mind’s eye. Then the light cut out, and she walked off the stage. After a period of stunned silence, one lone person nervously began to clap, and the whole audience joined. Many in the audience openly wept, and word quickly spread (Holiday 84; Clarke 164).

There are many versions of how Billie Holiday came to sing this song, and each tends to make its teller look especially relevant to the story (unsurprisingly, the white men make themselves out to be the wise ones, and Billie oblivious and obedient, something she herself contests in her biography). Despite conflicting interpretations, some facts seem clear. Abel Meeropol, a New York City schoolteacher, wrote the song under his pen name, Louis Allan. An avid poet and songwriter allied with progressive causes of the time, Meeropol supposedly saw a photograph of the infamous August 7, 1930 lynching of Tom Shipp and Abe Smith in Marion, Indiana. After Shipp and Smith were captured and charged with robbery, murder, and rape, an angry mob broke into the Grant County jail, brutally beat them to death, and hung them over a tree in the town square. Local photographer Lawrence Beitler captured a surreal scene that portrays some of the thousands who gathered for the spectacle: men in ties and banded straw hats, women in dresses, with one man in the center pointing upwards towards the bloodied bodies hanging limply from ropes thrown over branches in the tree (see Madison). Deeply moved by what he saw, Meeropol penned the poem and developed a melody for the song that he and a few others sang at school meetings and union gatherings.

While much of America was mobbing theaters to see Gone with the Wind, Meeropol asked—or was invited, depending on the story—to share the song with Holiday. Barney Josephson, manager of Café Society, negotiated the meeting. Again, accounts vary, but it is clear that despite others wanting credit for her decision to sing the song, it was Holiday herself who felt called to take it on despite real risks of retaliation. She recalled:

It was during my stint at Café Society that a song was born which became my personal protest—“Strange Fruit.” The germ of the song was in a poem written by Lewis Allan. I first met him at Café Society. When he showed me that poem, I dug it right off. It seemed to spell out all the things that had killed Pop. (Holiday 84; Davis 186)

In fact, her father, jazz guitarist Clarence Holiday, died just two years prior to her singing “Strange Fruit.” Suffering from exposure to mustard gas while serving in World War I, he became sick on tour in Texas and was refused treatment at the local hospital. By the time he was able to receive care on the Jim Crow ward of the Veterans Hospital, pneumonia had set in, and he died shortly after.

A lifetime of experience with such racially charged incidents gave Billie Holiday ample means to understand and resonate with the emotional edge of the song. Recalling her first (and only) opportunity at the big screen, opposite Louis Armstrong in New Orleans (1947), Holiday reveals her anger at discovering she would “star” in the role of a maid:

I thought I was going to play myself in it. I thought I was going to be Billie Holiday doing a couple of songs in a nightclub setting and that would be that. I should have known better. When I saw the script, I did. You just tell one Negro girl who’s made movies who didn’t play a maid or a whore. I don’t know any. I found out I was going to do a little singing, but I was still playing the part of a maid. (Holiday 119)

She made “Strange Fruit” her signature, even changing her contract to stipulate her right to perform the song as a protection against club owners who regularly sought to keep her from singing it. When her own mother, Sadie Fagan, worried about her safety and asked her, “Why are you sticking your neck out?” Holiday replied, “Because it might make things better” (Greene 61).

Billie Holiday knew that the song might not make her career better, no matter what long-term changes she might have hoped for in society. John Hammond, the talent scout who brokered her first recording contract on the Columbia label, went on record that singing the song was “artistically the worst thing that ever happened to Billie.” Drummer Max Roach, however, saw something else, something shared by many: “When she recorded it, it was more than revolutionary. She made a statement that we all felt as black folks.” The song’s author, Abel Meeropol, said that “Billie Holiday’s styling of the song was incomparable and fulfilled the bitterness and shocking quality I had hoped the song would have. The audience gave her a tremendous ovation” (Margolick 29).

New York Post columnist Samuel Grafton, deeply moved by the power of the song, wrote: “The polite conversations between race and race are gone. It is as if we heard what was spoken in the cabins, after the night riders had clattered by.” Indeed, the prominence of the song did lend energy to the decades-long battle by NAACP leaders and others to sponsor and pass a national anti-lynching law. Bills were introduced and passed three times in the House of Representatives; however, all three were stopped by filibusters in the Senate. It is a significant piece of the horror of lynching in the US that a national anti-lynching law was never passed as a result of this Senate inaction, and in 2005 the Senate publically apologized for this failure.2

Most of Billie Holiday’s songs were not directly political. They were songs about love and loss, typical subjects for popular music and for the blues in particular. In fact, “Strange Fruit” was released as a 78 recording with Holiday’s own composition as the “B” side. Titled “Fine and Mellow” and written the night before the recording session, the song’s theme ruminates on being treated poorly by her man. While only twenty-four when she wrote and recorded this song, Holiday had seen enough of life—her own and others—to sing powerfully from the experience of suffering.

Eleanora Fagan, Holiday’s birth name, was born in Philadelphia in 1915 to Sadie Fagan. Her father left before she was born and apparently didn’t acknowledge his paternity until she became famous many years later. Raised by her mother in Philadelphia and New York in very difficulty circumstances, Holiday recalls being raped multiple times before she was fifteen. During her teens, she worked as a prostitute, eventually spending a year in prison for solicitation. She had begun singing earlier in night clubs and brothels, but after prison finally got a break singing for tips in Harlem night clubs where Columbia Records talent scout John Hammond heard her. By age eighteen, she had recorded her first records, chosen for her and recorded with popular band leaders like Bennie Goodman.

As Holiday began to write her own songs, such as “Fine and Mellow,” she drew powerfully on the blues mode. Jazz great Winton Marsalis remarked:

When you hear Billie Holiday sing, you hear the spirit of Bessie Smith and Louis Armstrong together in a person, so you have the fire of the blues shouter, you have the intelligent choice of notes like a great jazz musician, but with her you have a profound sensitivity to the human condition. She tells you something about the pain of the blues, of life, but inside of that pain is a toughness and that’s what you are attracted to.

Perhaps her best live recording of the song was the live telecast of The Sound of Jazz, a CBS television program in December 1957.3 For the recording she reconnected with her old friend, saxophone great Lester Young. Dressed simply in a long black dress and white shirt and cardigan, Holiday took her characteristic stance half sitting, half standing on a stool amidst the instrumentalists. As the saxophones slowly swing into the sad tune marked by classic blues descending thirds, Holiday gently unfolds the first verse in AAB form:

My man don’t love me, he treats me oh so mean.

My man he don’t love me, he treats me awful mean.

He’s the lowest man, that I’ve ever seen.

Saxophone solos follow, including an incredibly moving and subtle solo by Lester Young, a solo clearly moving to Holiday whose facial expressions seem to reach out to urge him on.

If she was mostly known for light-hearted love songs like “It Was Just One of Those Things,” the blues as represented in “Fine and Mellow” were closer to Billie Holiday’s life experience. She did experience a series of abusive relationships with men, usually interwoven with her own abuse of drugs and alcohol, a sad fact that contributed to her death at the young age of forty-four. Yet her legacy has only grown since her death, a legacy rooted in her brilliant innovations as a vocalist and her willingness to use her career to raise “race” questions. She remarked on more than one occasion that “I’m a race woman,” and lamented that on tours, “I hardly ever ate, slept or went to the bathroom without having a major NAACP-type production,” a reality of the still-strong segregation policies in many regions where she traveled and played (Davis 193). Even in more progressive urban areas, white audiences could be impervious to her message, as when a woman at a Los Angeles club asked that Holiday sing “that sexy song you’re so famous for, you know, the one about the naked bodies swinging in the trees” (Holiday 84; Davis 193, 195). One understands something of the profound pain of her life in stories such as these. Such pain helps one understand her determination to take her stand concert after concert singing what may be the most moving, if horrible, love song of her career—a love song for her people rooted in the prophet’s cry against injustice.

Christian Scharen is Assistant Professor of Worship and Theology at Luther Seminary, St. Paul, Minnesota. He is currently writing Broken Hallelujahs: Imagination, Pop Culture, and God (Brazos Press 2009).

Why God Loves the Blues, Part II

Why God Loves the Blues, Part III

Works Cited

Clarke, Donald. Billie Holiday: Wishing on the Moon. New York: Da Capo, 2002.

Davis, Angela. Blues Legacies and Black Feminism. New York: Vintage, 1999.

Greene, Meg. Billie Holiday: A Biography. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 2007.

Holiday, Billie with William Dufty. Lady Sings the Blues. New York: Doubleday, 1956.

Madison, James H. A Lynching in the Heartland: Race and Memory in America. New York: Palgrave McMillion, 2003.

Margolick, David. Strange Fruit: The Biography of a Song. New York: Harper, 2001.

Marsalis, Wynton. Audio excerpt from Jazz: A Film by Ken Burns. http://www.pbs.org/jazz/biography/artist_id_holiday_billie.htm. Accessed on 29 July 2009.

Spencer, Jon Michael. Protest and Praise: Sacred Music of Black Religion. Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 1990.

Notes

1 Quoted in Spencer, 122.

2 Incredibly, after the horror of 4,742 recorded lynchings in American history, and undoubtedly more that were unrecorded, the Senate could not even pull off an on-the-record unanimous vote. In fact, the 2005 vote was a voice vote, so individual votes would not be recorded, and was co-sponsored by 80 of 100 Senators, a surprising tally. “It’s a statement in itself that there aren’t 100 co-sponsors,” said Senator John Kerry (D-Mass). Sheryl Gay Stolberg, “Senate Issues Apology over Failure on Lynching Law,” New York Times, 14 June 2005.

3 A video of this famous performance is available on YouTube at: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_tNSp7MaADM (accessed on July 29, 2009).