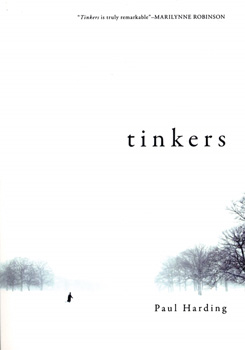

When Paul Harding won the Pulitzer Prize earlier this year for his first novel, Tinkers, the literary world gave a collective gasp of delight. The story was perfect: Harding, a graduate of the Iowa Writers Workshop, had written an inventive little novel, only to have it rejected by a number of well-known publishers. He published it, instead, with a small press. With a glowing cover blurb from Pulitzer-winner Marilynne Robinson, it was warmly received at independent booksellers but largely ignored by the literary establishment. The New York Times didn’t bother to review it. Then, it won the nation’s largest literary prize. The glass-slipper-shod Harding had, like that, ascended to the pinnacle of American literary achievement.

I understand why this novel was the darling of independent bookshops, why it won the Pulitzer, and why many critics are radiant with praise. I also understand why some avid readers I know haven’t made it through even its modest 191 pages. It is, for better and for worse, the first novel of a graduate from the nation’s most prestigious creative-writing program. For better, the novel has lovely prose, a complex structure, and important and interesting themes. For worse, it is a lot of work to read.

The novel counts down the last eight days of the life of George Washington Crosby. As George lies dying in his living room, his family gathers around him. He drifts in and out of consciousness and lucidity. Interspersed with his near-death experiences is background insight into George’s personality and narrates the stories of George’s father, Howard, and of Howard’s father, who is not named. The novel interweaves these accounts with quotations from an invented eighteenth-century clock-repair manual and poetic literary fragments from someone’s journal—perhaps Howard’s, perhaps Howard’s father’s.

One piece of literary showmanship that slows down the reading process, then, is Harding’s narrative voice. Or voices. Harding’s novel shifts voices a number of times, for reasons that are not always clear. The novel is mostly in the third person, past tense: “George Washington Crosby began to hallucinate eight days before he died.” It periodically shifts into first person, and Howard, George’s father, speaks in his own voice: “I should say that the sermons my father gave on Sundays were bland and vague.”

There are other shifts too, though, and they are occasionally perplexing. At one point, a minor character at George’s bedside speaks in the first person: “This is a book. It is a book I found in a box. I found the box in the attic…. The dust and the air was made up of the book I found. I breathed the book before I saw it; tasted the book before I read it.” Charlie, George’s grandson, seems at first to be speaking to himself. No one talks like this, least of all by a bedside, on limited sleep. Without any marked transition, however, it becomes clear that he is saying all this to his grandfather: “Do you want the bed down a little bit more?” It is clever, but jars the reader, for a moment, out of the comfort of knowing what is going on. Harding also shifts repeatedly between past and present tenses, particularly in the third section of the novel which narrates a crucial turning point in Howard’s childhood and a crucial turning point in Howard’s adult life.

I could usually find reasons for the shifting voices and tenses in the novel. Because Howard’s story—and character—is so central to the novel, perhaps he needs to speak for himself. A tinker in the late nineteenth century, he travels through the New England woods, ineptly trying to interest homesteading housewives in his wares. He routinely gets distracted by the beauty of the natural world and falls into a kind of poetic reverie. The story of Howard’s life is the dominant narrative of the novel. And Howard’s story—his experience with epilepsy, his memories of his own father, a crucial moment of high drama during George’s childhood—is compelling. If Howard is a writer, then the novel’s impulse to let him speak makes some sense.

There are likewise plausible justifications for the other voices in the novel. Howard’s father is a writer, too, a “strange and gentle man” who spends his days “in the room upstairs at the walnut desk tucked under the eaves, composing.” Perhaps the book that Charlie describes (and then reads) to George is Howard’s father’s journal. The entries, with mysterious headings like “Cosmos Borealis” and “Crepuscule Borealis” are full of lush, evocative, descriptive prose: “Skin like glass like liquid like skin; our words scrieved the slick surface (reflecting risen moon, spinning stars, flitting bats), so that we had only to whisper across the wide plate.” If the selections are from Howard’s father’s journal, they make certain plot and thematic elements in the novel more poignant. They are not easy to understand, however, and the hints about their significance are oblique at best.

There is also something clever and appropriate about the selections from The Reasonable Horologist that Harding sprinkles throughout the novel. George, in his retirement, has taken to repairing antique clocks. He tinkers with the mechanisms, as his father tinkered in the New England woods. While the lives of his father and grandfather were full of chaos and rupture, George’s life is one of order and control. He’s a practical, careful person. As his life winds down, he can be content that he has acted reasonably. We discover that George has stashed cash away, methodically, in safe-deposit boxes throughout New England that his wife will use to live comfortably after his death.

But although the selections from The Reasonable Horologist can be accounted for thematically, they are yet another interruption in the novel, another element that disorients. Perhaps Harding would say that interruption and disorientation are thematically essential to this story of a man’s death. As George’s life unwinds, as his brain ceases to make coherent sense of his surroundings, the reader experiences this as well. As a teacher of literature, I can accept this; it is an answer I might give to my students. As a reader, however, I reject it. I lost patience with this novel a number of times and got tired of working to make sense of what was going on.

This is a beautiful novel, especially at the sentence level. Harding, who admires the transcendentalists, describes in finely wrought prose many mystical encounters with the physical world. Each of the main characters in the story is afflicted in some way that is a source of transcendent experience and fodder for evocative description. As George dies, Harding gives us sparse but compelling metaphors, describing the transformation of his body from living to dead: “His bloodless legs were hard like wood. His bloodless legs were dead like planks. His bone-filled feet were like lead weights that were held by his dried veins—his salt-cured, metal-strengthened veins, which were now as tough as gut, and strong as iron chains.” Howard, for his part, suffers from epilepsy: a “secret door that opened on its own to an electric storm spinning somewhere on the fringes of the solar system.” Howard’s father, a minister, who obsessively composes up in his attic room, deteriorates into madness or dementia. The reader experiences this process from the perspective of Howard who tells us that: “The end came when we could no longer even see him, but felt him in brief disturbances of shadows or light, or as a slight pressure, as if the space one occupied suddenly had something more packed into it.” The rupture of Howard’s father’s mind is thus a source of transcendent experience for his son.

All three men struggle with their relationship to their own embodiment: George, because he is dying; Howard, because he is an epileptic; Howard’s father, because he is mad. Their stories are affecting. Some readers, however, will not get far enough to come to care. Some will lose track of the narrative threads in the shifting voices, tenses, and genres before they get to know George, Howard, and Howard’s father.

Tinkers will naturally be compared to the novels of Marilynne Robinson. After all, Robinson wrote the glowing blurb. Harding studied with her and was inspired by her to read great works of theology. They both wrote prize-winning first novels, and both wrote novels about older men and their relationships with their fathers. Though they are a generation apart, the connections between the two are evident.

Thematically, Tinkers is most similar to Gilead, Robinson’s second novel. Both are novels about fathers and sons and about mortality. In terms of craft, however, a comparison with Robinson’s first novel, Housekeeping, is more apt. Housekeeping, a first novel which also won a top award (PEN/Hemingway) is also more experimental and less reader-friendly than the later Gilead. Tinkers may frustrate some readers, and I will not blame those who toss it aside as too showy and labored. But, trusting the comparison with Robinson, I have high hopes for his second novel.

Susan Bruxvoort Lipscomb is Assistant Professor of English at Houghton College.