Athena Kildegaard: Review by Lesley Wheeler

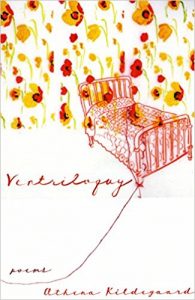

Athena Kildegaard, Ventriloquy (Tinderbox Editions)

From Grief to Joy: A Review of Ventriloquy

“Is art only mourning?” Athena Kildegaard asks near the end of Ventriloquy, her fourth collection. Certainly, as she writes in the prose poem “Still Life with Tides,” art can be “a cry for what is and how it will be no more.” Poets, in particular, mourn and remember endlessly. Poetry requires acts of close attention, rooted in a sense of how fast the world changes and how much we lose if we don’t pay mind.

But is poetry only grief? It’s funny that this elegantly framed question occurs in such a joyful, even festive book. Ventriloquy is a riot of flowers and saints and sexy fruits. Its implicit argument, in fact, links poetry not with mourning but with desire: human beings’ eros and spiritual yens; botanical reaching after light; even the eye’s hunger for wild meanings latent in tame scenes. In this collection, further, desires are projected onto all creation via ventriloquy—voiced, that is, by various unlikely parties. Maybe yearning and grieving are two sides of the same coin, but if I had to choose, I’d say Kildegaard’s book emphasizes desire over death in almost every line.

A deeply patterned, symmetrical collection, Ventriloquy is arranged into five sequences—four, really, since parts two and four, both titled “Saints, Contrary and Futile,” are split halves of a whole. Kildegaard begins with a bouquet of flower poems, each named after a kind of blossom and comprised of eight free-verse lines. This is in many ways a deeply traditional move. The garden is an ancient literary metaphor redeployed by a host of women poets, including Emily Dickinson, H.D., Louise Glück, Rita Dove, and Medbh McGuckian, just for starters. What won me over to Kildegaard’s flower-poetry was the freshness of her language: she jars familiar tropes while wrestling productively against the self-imposed smallness of her form. A plucked daisy becomes a “stylus of desire”; fuschias are “wives of plumbers and electricians”; and “The Hydrangeas” involves feather boas, cloisonné chargers, and a poodle tied to a clothesline. Her take on “The Roses” is witty and unexpected—not easy, to write well about that most traditional flower-symbol—while “The Gardenias,” printed below in its entirety, is more disturbing:

After the waters receded, on sodden

grass, carcasses lay bloated,

bottleflies gorged, their swollen

thoraxes glistening in the sun.

Languid snakes found heat

on peeling refuse, and unfolding

in flesh, the gardenias, their thick

scent wafting, bloomed: a new eden.

“The Gardenias” seems to be a post-Katrina poem from nature’s point of view, in which dead bodies are no more remarkable than any other element of a landscape after flood. Kildegaard’s gardens are not havens from a violent world. The anger is there; it’s just transformed.

While the first portion of Ventriloquy dwells on earthly desires, the “Saints” sequence focuses on what we worship. More various in verse styles, these poems likewise mingle lush imagery with politics, but here the scent of religious ecstasy is more heady. Many of the patrons saints Kildegaard singles out, however, are distinctly secular despite the ardent believers they inspire: Big Data, efficiency, plastic, and, in “The Citizen Saint,” U.S. gun culture. Nor does Kildegaard exempt herself from all the erotically-tinged pseudo-religious mania. “In the Word Saint,” she takes on linguistic obsessions—an apt topic for a word-drunk collection, driven by rhythm and rhyme, words’ sounds and textures. As addictions go, a love of language seems pretty harmless. Yet every hoard represents an anxious “surety against disaster,” a bulwark against death, even against real contemplation. Despite her piling up of verbal curiosities, “the word saint never formed whole thoughts,” the poet observes. I love how, as the waters ominously rise at the end of “The Word Saint,” most of the verbiage washes away:

See word see word see word

she shouted

as she floated off bobbing a little

bobbing and bobbing,

shouting, bobbing.

In the end, words can’t save us any more than Big Data can.

My favorite sections of Ventriloquy are the middle sequence, “Divination,” and its final one. The question at stake in “Divination” is something like, What will become of us? Kildegaard invites us to divine the future by interpreting a series of peculiar texts. In “By Sighs,” a teenage girl is “nothing but vowels”: just try reading her metaphorical palm! The iron in “By Iron” is a cousin’s erection, a more legible signifier. In “By Beads,” the hieroglyphs involve yet more hoards and collections—rubber bands and paper clips—because the collector is a worrier trying “to hold the world together.” Pronouns remain slippery, but these poems feel more narrative and autobiographical than much of the book.

The brief character studies in “Divination” are especially gorgeous, yet the book’s final sequence of right-justified prose poems, “Still Life with Universe,” lingers with me most powerfully. The imaginary compositions each verbal “still life” describes are recognizably painterly: a trout “egg-plump and delicately brindled”; “runcible spoon, a quill, a tankard, two ripe quince”; “a glass shaker fallen onto the pink cloth, pepper thrown, a galaxy, a startled flock, a Braille riddle.” Yet just as that last quote tries out a series of metaphors for spilled peppercorn fragments, each poem in “Still Life with Universe” suggests double vision, a scene beyond the scene at hand. Often an indoor arrangement inspires outdoor visions. The spilled peppercorns poem, in fact, is called “Still Life with Passenger Pigeons.” Another table with a pink spread evokes tectonic plates; an inkwell becomes a distant oil rig. The domestic universe, women’s traditional sphere, is not small. Poems can contain worlds.

I’m not sure I understand all the forces in operation in this beautiful sequence, but its climax is suggestive. The third to last poem, “Still Life with My Mother, Dead Now Three Months,” evokes strong emotions via a few spare images: a prickly branch of gooseberries sits on a table and a single lily stands in a thin vase, “petals fleshy and expressive.” Here is mourning, fruition, maybe even resurrection, but as the speaker herself reflects, “So much is hidden.” Nor do the last two poems, “Still Life with Universe” and “Still Life with God,” reveal answers. A poet can describe some of what she sees, but the whole view is unavailable. The main thing to understand is that looking defines us. As long as we live, we yearn to know. “Otherwise,” as Kildegaard writes in the book’s very last sentence, “the painting is unfinished.”

Maybe the intense repetition in this book—forms, images, strategies returned to as if compulsively—is, in fact, rooted in mourning. Maybe Kildegaard even gave herself daily writing assignments to work past grief, boiling down the results to these luminous sequences. I don’t know, but rather than seek a real-life answer, I find myself preferring enigma. The effect of all this accumulation is prayerful. In Ventriloquy, writing is a spiritual practice, joyfully observed.

When I teach Whitman and talk to students about the experience of reading his long catalogues, a few of them always guiltily report eye-skips. Anaphora, that is, undercuts attention, charming the ear so much that the mind ceases to track meaning or register surprise. The repetitions of Ventriloquy sometimes had a similar effect on me: the good made it harder to see the great. This is a flaw in the reader, not the book, but it’s worth mentioning, because others may experience these sequences in a similar way. My advice is to accept Kildegaard’s challenge to find surprise in recurrence. There’s freshness, mystery, and hard thinking here. Don’t be lulled into missing it.

Lesley Wheeler’s fourth poetry collection is Radioland from Barrow Street Press. A Fulbright scholar and the Mid-Atlantic Council Chair for the AWP, she teaches at Washington and Lee University.