~EDWARD BYRNE~

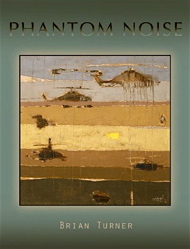

WALKING

AMONG THEM: BRIAN TURNER’S PHANTOM NOISE

One of the ways Brian Turner has responded

to his history,

as a soldier at the battlefront who returns home, has been

to explore in his poems various experiences encountered

in a war zone and to examine the enduring emotions evoked

by them. Indeed, early in his new collection of poems,

Phantom Noise,

Turner reminds readers of how frequently

soldiers encounter an inability to leave behind the traumatic

images and dramatic experiences of war.

After Brian Turner’s first book of

poetry (Here, Bullet: Alice

James Books, 2005) concerning contemplations about the circumstances

surrounding war was published, many readers discovered that the

collection contained marvelous works exhibiting a poet-soldier’s

individual and vivid images. Written in concise lines of poetry that at

times appear intimate yet often also maintain an ability to present a

bit more of the differing perspectives of other Americans or Iraqis

ensnared by the circumstances of combat and survival, the poems

frequently offer personal considerations and experiences that somehow

have struck a widespread interest and have assumed a somewhat greater

public significance in the handful of years since their release.

Turner, who served seven years in the U.S. Army,

including tours of duty in Bosnia-Herzegovina and then Iraq, is also an

MFA graduate from the University of Oregon’s creative writing program.

With Here, Bullet Turner

followed in the footsteps of other American writers who have eloquently

recorded emotionally charged front-line observations during a time of

war. Indeed, Walt Whitman, Ernest Hemingway, and Tim O’Brien seem among

the primary influences on Turner (the Vietnam War poems of Bruce Weigl,

Yusef Komunyakaa, and John Balaban surely also play a part). In

interviews Turner has acknowledged a debt to O’Brien’s works

(especially Going After Cacciato),

and like O’Brien in his fiction, this poet often focuses on details

that lend a persuasive sense of authenticity or authority to the voice

in the poems, even when pieces involve fanciful scenes or surreal

dream-like narratives.

Recognition of Hemingway’s influence appears early

in the book, as a quote from Papa opens the initial poem: “This is a

strange new kind of war where you learn just as much as you are able to

believe.” Throughout the poetry in Here,

Bullet Turner displays his attempts at understanding the

conditions in which he, his fellow soldiers, and the Iraqi citizens

must endure day after day in order to survive. He wants to believe the

terrible sacrifice of lives will be worth it in the end; however, by

the final poem in this volume readers witness indications Turner has

lost all hope the cost of the war will be warranted, let alone rewarded

by a better future. soldiers, and the Iraqi citizens

must endure day after day in order to survive. He wants to believe the

terrible sacrifice of lives will be worth it in the end; however, by

the final poem in this volume readers witness indications Turner has

lost all hope the cost of the war will be warranted, let alone rewarded

by a better future.

Like the wounded Harold Krebs in Hemingway’s

“Soldier’s Home,” who comes back from combat and reads books about his

battlefront, seeing in them a different war than the one he

experienced, Turner’s speaker in “Ferris Wheel” comments: “The history

books will get it wrong.” Nevertheless, one of the most important

characteristics of this volume remains Turner’s almost complete

avoidance of any overtly political commentary or editorializing,

reserving his sole focus for the presentation of powerful actions and

clearly depicted individuals, allowing readers, if they wish, to form

their own opinions on political concerns or controversial issues.

Admirably, Turner tries to offer different versions

and to identify distinct visions of the events related throughout the

book by learning various aspects of local language, customs, and

religious beliefs. The speaker in these poems desires a way to

understand and empathize with those whose country is caught in the

crossfire of conflict. Indeed, in published comments Turner has voiced

great admiration for the writings of Balaban, particularly Remembering Heaven’s Face, a memoir

about his relationships with the Vietnamese people he met — learning

their language, literature, and culture — during a time in which he

volunteered to work in the war zone even though he’d been granted

conscientious objector status. Readers can appreciate Turner’s

compliment to Balaban just as they also may appreciate the

complementary elements in each author’s approach to the subjects in

their writings.

Some of the poems in Here, Bullet seem like contemporary

camp scenes reminiscent of the Civil War campfire poems by Walt

Whitman, as soldiers are portrayed in ordinary circumstances while on

base or enjoying a lull after curfew. In “Cole’s Guitar” Turner’s

language most closely resembles Walt Whitman’s voice when he catalogs

images of America evoked by the sound of a comrade’s six-string. “I’m

hearing America now,” Turner writes as he lists various everyday events

he imagines taking place back home. By the final lines of the poem

(which is recorded as taking place in Al Ma’badi, Iraq), Turner’s

speaker reveals seeing strangers’ faces “the way ghosts might visit the

ones they love, / as I am now, listening to America.”

Although, as with almost all first books of poetry

(perhaps one could just as easily say “all books of poetry”), there is

a selection of poems that clearly stand as the strongest in this

collection, a number of compelling compositions that draw the reader

from the opening piece introduced by the Hemingway quote through to the

closing work in the book. However, one poem in Here, Bullet deserves to be

identified not only as an outstanding work in this volume, but also as

one of the finer pieces by any poet in recent years. “2000 lbs.” is a

poem that freezes in time the moment a terrorist suicide bomber

triggers his explosives in a town square of Mosul. In sectioned

passages of the poem, Turner provides readers with brief profiles

introducing some of the victims in the blast — what they are doing,

what pasts they have experienced, whom they love and by whom they are

loved, what hopes for the future they hold, where they are headed —

when their lives are suddenly and shockingly destroyed.

Among the victims arbitrarily targeted are American

soldiers, as well as Iraqi men and women, including one old woman who

“cradles her grandson, / whispering, rocking him on her knees / as

though singing him to sleep.” Consequently, in addition to fixing in

time an isolated moment of horror in the center of a war zone, Turner

also aptly captures an iconic act emblematic of an entire period of

history. Few poems show such potential for moving readers so

emotionally while at the same time inviting intellectual and ethical

reflection, requesting that readers investigate the tenuous thread by

which any life hangs.

By the time readers reach the final poems in this

collection, they are left to consider unanswered questions similar to

those raised by the speaker of “Night in Blue,” thoughts that also must

linger in the minds of soldiers returning home from the war zone: “What

do I know / of redemption or sacrifice, what will I have / to say of

the dead — that it was worth it, / that any of it made sense?”

In an article, “To Bedlam and Back,” that appeared

in the New York Times last

October, Brian Turner wrote about the difficulties facing soldiers when

they make the transition from war to home. Even as a veteran, an

infantry sergeant who served both in Bosnia-Herzegovina and in Iraq,

Turner questioned his own perspective on this issue: “I guess what I’m

wondering most is, as a country that is currently at war, how do our

veterans rejoin the life waiting for them back home? How do they rejoin

the tribe once they’ve been to Bedlam? How do we help them so that they

don’t feel as if they’re encased in glass, pinned to the walls as

specimens in some museum-house of culture? It’s a difficult question to

answer. I have trouble answering it myself.”

One of the ways Brian Turner has responded to his

history, as a soldier at the battlefront who returns home, has been to

explore in his poems various experiences encountered in a war zone and

to examine the enduring emotions evoked by them. Indeed, early in his

new collection of poems, Phantom

Noise, Turner reminds readers of how frequently soldiers

encounter an inability to leave behind the traumatic images and

dramatic experiences of war. Even when engaged in an everyday activity,

such as shopping at the local hardware store, a veteran seems haunted

by his past in a combat zone:

Standing in aisle 16, the hammer

and anchor aisle,

I bust a 50 pound box of

double-headed nails

open by accident, their oily

bright shanks

and diamond points like firing

pins

from M-4s and M-16s.

In a steady

stream

they pour onto the tile floor,

constant as shells

falling south of Baghdad last

night, where Bosch

kneeled under the chain guns of

helicopters

stationed above, their

tracer-fire a synaptic geometry

of light.

At dawn, when the shelling stops,

hundreds of bandages will not be

enough.

[“At Lowe’s Home Improvement Center”]

Similarly, in “Perimeter Watch” a soldier who has

returned home remains guarded against an imagined battlefield scene: “I

lock the door tonight, check the bolts twice / just to make sure. Turn

off all the lights. / Only the fan blades rotate above, slow as

helicopters / winding down their oily gears.” He believes he can detect

water buffalo on his lawn, and when the sprinklers around his house

begin to operate, he thinks “cowbirds lift up from the grass / with

heavy wing-beats, a column of feathers.” The speaker confides:

Through

venetian blinds

I see the Iraqi prisoners in that

dank cell at Firebase Eagle

staring back at me. They say

nothing, just as they did

in the winter of 2004, shivering

in the piss-cold dark,

on scraps of cardboard, staring.

“Perimeter Watch” concludes with a brief but

compelling closing stanza: “When I dial 911, / the operator tells me to

use proper radio procedure, / reminding me that my call sign is Ghost 1-3 Alpha, / and that it’s

time, long past time, to unlock the door / and let these people in.”

Even in sleep, or perhaps especially in that state

when figures rise from the subconscious, the psychologically wounded or

searching speakers in Turner’s poems cannot escape the harsh memories

and emotional moments encountered in war. The opening of “Illumination

Rounds” introduces evidence of long-lasting damage:

Parachute Flares drift in the

burn time

of dream, their canopies deployed

in the sky above our bed. My lover

sleeps as Iraqi translators

shuffle

in through the doorway—visiting

as loved ones might visit a

hospital room,

ill at ease, each of them holding

their sawn-off heads in hand.

Later in the poem the lover finds Turner’s speaker

“at 3 A.M., shoveling / the grassy turf in our backyard, digging /

three feet by six, determined to dig deep.” The veteran tries to

convince his love that “the war dead” are still present, and he

attempts to get her to see them, “how they stand under lime trees and

ash, / papyrus and stone in their hands.”

Instead, she persuades him to halt his shoveling and

advises: “We should invite them into

our home. / We should learn their names, their history. / We should

know these people / we bury in the earth.” Nevertheless, in the

poem’s final section the speaker endures another painful flashback as

he drives the familiar roads in his home community:

I’m out on patrol again, driving

Blackstone to Divisidero, Route

Tampa

to Bridge Number Four, California

to the neighborhoods of Mosul,

each stoplight

an increment, a block away from

home

and a block closer to the August

night

replaying in my head.

By the time the poem reaches its end, the speaker

confesses to a continuation of his past trespassing on the present, as

he reports hearing “gunshots echoing years later, the incoherent /

screaming I’ve translated a thousand times over, / driving until I

finally understand / who it is I’m supposed to kill.”

The persistence of the past, including its seemingly

unending memories of misery and moments of despair associated with war,

is evoked through the book’s title poem in which the author employs the

technique of word repetition and the form of a single unpunctuated

stanza without any end-stopped lines, including the final one. The

“Phantom Noise” heard by the narrator consists of a constant “ringing

hum” he cannot avoid, one that echoes sounds so familiar from wartime

events: “bullet-borne language”; “ringing / shell-fall and static”;

“broken / bodies ringing in steel”; “ringing / rifles in

Babylon rifles in Sumer / ringing”; “ringing of midnight in

gunpowder and oil,” etc. The

“Phantom Noise” heard by the narrator consists of a constant “ringing

hum” he cannot avoid, one that echoes sounds so familiar from wartime

events: “bullet-borne language”; “ringing / shell-fall and static”;

“broken / bodies ringing in steel”; “ringing / rifles in

Babylon rifles in Sumer / ringing”; “ringing of midnight in

gunpowder and oil,” etc.

This ringing reminds the speaker of “children their

gravestones / and candy their limbs gone missing,” and he recalls the

“muzzle-flash singing this / threading of bullets in muscle and

bone.” The poem closes with little or no hope that the ringing will

ever stop, “this ringing / hum this ringing hum this

ringing hum this / ringing”

However, this remarkable collection of poetry

manages to move forward, to embrace the present despite the formidable

pull of past events. Indeed, Turner’s new book appears to display the

necessity for one to accommodate the past in the present as a way of

understanding that will eventually allow an advance into the future

with a greater degree of confidence.

Beyond the poems about Iraq and other recent events,

many of the works in Phantom Noise

are identified with specific time periods in the past, some personal

memories and others historical happenings, a few more distant than

others. “Homemade Napalm” features a “Winter,

1978” designation as the speaker relates details about his

father and grandfather in an era after a different war: “He drank

coffee, / saying nothing of my grandfather, / the Marine, Guadalcanal,

the flamethrower / carried on his back. He didn’t need to.” Another

poem, “Bruce Lee’s Enter the Dragon,”

begins in the same time period: “I drank a Seagram’s Seven and Seven on

7/7/77, / when I was only ten and my mom a bartender.” In the opening

lines of “Lucky Money,” the speaker declares: “It is 1971. / At Willie

Lum’s Hong Kong Restaurant / I’m four years old . . . .” Similarly,

“The Whale” starts with a childhood recollection: “It is 1970 / and the

summer of love is over. // I am three years old, barefoot, / running

along the surf / near Florence, Oregon.”

Elsewhere, the poet locates “.22 Caliber” in “1981.

The Soviets fight in Afghanistan.” Still, in a couple other powerful

poems Turner glimpses much further back in history for incidents and

information that might aid with an understanding perhaps necessary for

him to step forward into the future. In “Ancient Baghdad” the author

reveals intensity in the poem’s initial descriptions:

Ash blackened the sky in 1258,

blood

ran in the rivers of Dajla and

Farat,

the House of Wisdom burned to the

ground

and the caliph was trampled to

death by horses.

This was ancient Baghdad, July,

and hot.

After 50 days of siege and 40

days of plunder

800,000 lay dead in the streets,

beheaded

by Mongols, many bodies thrown to

the river.

Some hid in wells and sewers.

Later, they rose from the stench

to walk the wailing streets,

where wild dogs

slept with tongues panting,

bellies swollen.

“Al-A’imma Bridge,” an ambitious and extraordinary

poem in the same category of outstanding works as “2000 lbs.” in Here, Bullet, contains a number of

references as it travels through various stages “in history’s bright

catalogue.” Readers are reminded of “laser-guided munitions directing

the German Luftwaffe / from 1941, Iraqi jets and airmen from the

Six-Day War, / the Battle of Karbala, the one million who died fighting

Iran; // and Alexander the Great falls, and King Faisal, / and the

Israeli F-16s that bombed the reactor in ’81.” A number of other years

are included among the litany in this poem:

the year 1956 slides under, along

with ’49 and ’31 and ’17,

the month of

October, the months of June, July, and August,

the many months to follow, each day’s exquisite

light,

the snowfall in Mosul, the

photographs a family took

of children

rolling snowballs, throwing them

before licking the pink cold from their fingertips.

Years unravel like filaments of

straw, bleached gold

and given to

the water, 1967 and 1972, 2001 and 2002:

What will we

remember? What will we say of these?

The speaker even retreats again to the historic

moment mentioned in “Ancient Baghdad”: “the dead from the year 1258

read

from the ancient scrolls / cast into the river from the House of

Wisdom, / the eulogies of nations given water’s swift erasure.” Seeking

illumination concerning the human history of conflict through

examination of evidence left by those who have gone before us, Turner

seems to believe confronting sins of the past possibly can assist in

liberating individuals from pain felt in the present, especially as

they peer with uncertainty into a distant vista acting as camouflage

that conceals what the future may hold for them.

Despite the numerous descriptions of death or

desolation and images of despair one naturally expects to find in

recollections of war, Brian Turner also presents brief hints of hope in

his poetry. In “Helping Her Breathe,” a soldier tries to filter the

sounds of battle surrounding him (“Subtract each sound. Subtract it

all.”) as he assists a woman in childbirth. Following two stanzas in

which the speaker lists the noises of war — “decibels of fighter jets,”

“skylining helicopters,” “rifle reports,” “hissing bullets,” etc. — a

final pair of stanzas emphasizes the quiet moments in a woman’s labor

and “the hush we have been waiting for.” The closing scene in the poem

beautifully provides readers with a symbolic situation of life and hope

so rare in such conditions:

She is giving birth in the middle

of war—

the soft dome of a skull begins

to crown

into our candlelit mystery. And

when

the infant rises through

quickening muscle

in a guided shudder, slick in the

gore

of birth, vast distances are

joined,

the brain’s landscape equal to

the stars.

Turner also offers an exquisite example of lyrical

description in a poem titled “Eucalyptus,” which begins with an

epigraph quoting Harry Mattison: “The

grace of the world survives our intervention.” The tone

suggested by this statement seems apt as it is attached to a brief but

precise poem evoking the environment of Mosul at dawn — not just “the

brain’s landscape,” but the physical landscape of the countryside: “a

dense fog / hangs in the eucalyptus grove. / Water buffalo / lift their

heads from the belly-high grass, nostrils / wet and shining, to breathe

in the damp smell of the earth.” By the final lines of the poem, among

the trees, “shadows in the half light of dawn” appear to be “forms / of

men, women, children” in the new day’s illumination: “the small bright

lanterns of sunlight / breaking through the leaves above.”

As the collection nears its conclusion, a few poems

invite more optimism for the future even though darkness continues. In

“Study of Nudes by Candlelight,” the speaker again uses an image of

shadow and light as he remarks:

I can see from this day forward,

how you carry my shadow in the

gloss

of your skin, without complaint,

the promise

of light dripping from your

fingers,

your wine-dark nipples, my lips

kissing your own, farther and

farther away.

The volume’s penultimate poem, “In the Guggenheim

Museum,” introduces a narrator and his lover touring the art exhibits

along a curving ramp in the building designed by Frank Lloyd Wright,

itself an artwork. While observing those objects representing the past,

the speaker reminisces about a romantic moment the lovers spent

together in a park the night before: “a breeze might lift / the tips of

her hair, my fingers guiding / the zipper in its channel, tooth by

tooth, / the way it did last night, in the park, long after / closing

time when the sprinklers switched on, / and we didn’t stop.” With

thoughts of love and memories of passion, he seems to realize a renewed

desire to appreciate life:

this is what I’m thinking about

in the museum,

the skeletons of art hung around

us, petrified,

staring through the hard lenses

of framing and oil,

staring at us from their

fossilized stations

in the past, in wonder, marveling

at

these two lovers, here, each of us

fully given to the inexorable

process

of death, and yet, here we are

walking among them—alive.

Once more, readers are given an image of the speaker

in a poem aware that he is walking among evidence of the dead and his

own mortality; however, the recognition of life and the necessity of

taking advantage of all living offers, especially an opportunity for

love, are emphasized in the work’s italicized final word. Regardless of

the many instances of death and pain one may witness along the way,

perhaps even feelings of guilt, particularly in war, there are

significant reasons to rejoice in life and declare forcefully in

affirmation to the value of being alive.

Appropriately, “The One Square Inch Project,” the

last poem in Phantom Noise,

contains contemplation concerning some of the elements previously

encountered throughout the collection: life and death, love and loss,

light and shadow, sound and silence, past and present, the physical

landscape and the brain’s landscape, memory and understanding. One

might be reminded again of the influence of Ernest Hemingway—whose

epigraph began Here, Bullet —

and recall the meditative mood brought about by being alone among

nature in Hemingway’s “Big Two-Hearted River,” as the speaker of this

poem explores the deep and silent nature discovered in Olympic National

Park, following a footpath through “deadfall and leaf rot.” He declares

such a setting as “a type of medicine by landscape.”

The reader is placed amid startling scenery,

demonstrated through a series of delicate painterly descriptions:

“auburn leaves of mountain ash, variations of maple, / aspens in gold

and rust and creamy yellows — all given to memory, / hushed by the

green

work of water; moss, vines, forest canopy.” Suddenly, the speaker

shares a surprising comment, an admission especially difficult to

believe when delivered by one so eloquent, so perceptive and clearly

adept with poetic language: “there is not one thing I might say to the

world / which the world does not already know.” However, such a

conclusion allows for the book’s final passage, which acts almost as a

summary statement for the whole collection:

I sit. And I listen.

When I return

to California,

to my life with its many

engines—I find myself changed,

the city somehow muted, frenetic

and fully charged with living, yes,

but still, when gifted with this

silence, motions have more

of a dance to them, like fish in

schools of hunger, once

flashing in sunlight, now turning

in shadow.

Although back home, thousands of miles in distance

and years later in time, the speaker cannot leave behind the

experiences and emotions accumulated during his tours in a war zone. He

finds himself changed, acknowledging the presence of sunlight and

shadow, as well as the persistence of memory. Nevertheless, he must

move forward. Turner’s words in the New

York Times article quoted above

come to mind once more: how do our

veterans rejoin the life waiting for them back home?

How do they rejoin the tribe once they’ve been to Bedlam?

In “Jundee Ameriki,” a poignant poem that explains

the circumstances for a soldier who has returned to California after

having been wounded in an attack by a female suicide bomber in Baghdad

on a cold

afternoon in November of 2005, the reader learns how shrapnel still

must be surgically extracted at a VA hospital periodically: “Dr.

Sushruta scores open a thin layer of skin / to reveal an object

traveling up through muscle. / It is a kind of weeping the body does,

expelling / foreign material, sometimes years after an injury.” This

poem seems a sequel to “2000 lbs.” as it chronicles lingering physical

injuries in the aftermath of such an incident that might mirror the

emotional impact lasting long beyond a soldier’s return home from the

front. Just as much of Phantom Noise

blends the domestic and exotic, the present and the past with an eye

toward the uncertain future, many of this new book’s poems represent a

bridge back to those works in Here,

Bullet. These latest poems link the two existences that continue

together, often in conflict, in the minds of their speakers.

Like the soldier in “Jundee Ameriki,” Brian Turner’s

speakers continually reveal fragments of wartime memories and emotional

scars, bits of the past that rise to the surface long past the

wounding. Yet, each seems to learn a lesson, that the past must be

absorbed and understood before it can be brought to light and expelled.

Moreover, one must grasp the need to carry on despite the enduring pain

caused by such remnants, like he “who carries fragments / of the war

inscribed in scar tissue, / a deep, intractable pain, the dull grief of

it / the body must absorb.”

Brian Turner’s Phantom

Noise presents evidence once more of that powerful and

compelling voice with which readers first became acquainted in Here, Bullet. With this new

collection of poetry, Turner fulfills the promise so clearly

demonstrated in his earlier volume, and he adds greater depth to

readers’ understanding of the circumstances or emotional conditions in

which his personae find themselves, many inhabiting lives forever

influenced by experiences or individuals — including a number of the

dead — from the past and still directing much of their present state of

mind as the poems’ speakers walk among them in their memories.

As those personages in Turner’s poems continue to

seek

comprehension and continually exhibit compassion, walking among ghostly

figures to learn lessons from

the past and leading readers in contemplation about the present, they

also engage in the continuous task of looking forward toward a fragile

future, perhaps absorbing grief and moving ahead with some uncertainty,

but undoubtedly walking onward with hints of hope and helped by love. Phantom Noise is an enlightening

and intriguing contribution to contemporary poetry that reaffirms the

talent readers first observed in Brian Turner’s debut

book. This rich and resonant new volume proves Brian Turner now has

firmly earned a position as

one of the nation’s more valuable poets.

Phantom Noise, Brian

Turner. Alice James Books, 2010. ISBN: 978-1-882295-80-7 $16.95

© by Edward Byrne

|

![]()

![]()

![]()