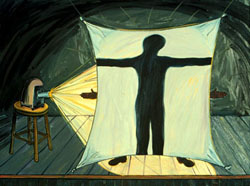

TIMOTHY VAN LAAR: SHADOW PICTURES

Like all artists who

feel the

need to express the inexpressible through highly

personal creative

products, Van

Laar manipulates his chosen images

to communicate the idea

that

all works of art, faithfully and sincerely

produced, are

manifestations

of the artistâs spirit. The desire to celebrate

and comprehend pure

beauty and

the quest to express oneâs admiration

and gratitude for that

beauty

lead the artist down a path of humility.

Timothy

Van

Laarâs painting Shadow Pictures is one of the Brauer

Museumâs most

popular pictures, due to not only the workâs striking composition

and lively

surface, but also its enigmatic subject matter. Richard Brauer,

the

director of the museum at the time of its acquisition, admired the

paintingâs

stylized mode of representation but was primarily drawn to its

puzzling,

fascinating handling of a Christian message. Van Laarâs

work invites

the viewer to look at the curious spiritual scenario and attempt to

understand

what exactly is happening on this symbolic stage.

Before,

however, addressing the subject matter of the work, one should

concentrate

on the representational style that Van Laar uses here. His

paintings

from the 1980âs are characterized by a stylized figuration, very

different

from his more abstract, atmospheric current work.

Objects depicted in the

picture

are highly simplified in a manner reminiscent of comic illustration,

childrenâs

books, or even medieval art. Such a simplification suggests that

objects or figures are not meant to be thought of as specific or

portrait-like;

rather, these items are visual reminders or symbols of ideas, with the

overall message of the work more important than a focus on any of its

components.

However, unlike illustration of various types (and unlike

the precious surfaces of

medieval

paintings, which, although highly stylized in representation, are rich

with gold leaf or jewel-like layers of tempera), Van Laarâs

painting has

a painterly surface, with glistening passages of oil paint brushed

wetly

across the canvas, sometimes blending but mostly staying boldly and

distinctly

within forms to give the work its graphic character. Thus, Shadow

Pictures has an illustrative feel to it due to the clear and

distinct

nature of the represented items in the picture. The ambiguity of

the depicted actions, though, coupled with the delightful surface

removes

the work from the illustrative realm and places it firmly in

artâs more

intuitive, metaphorical area of concerns. Van Laar reduces his

scene

and mode of representation

to their

essentials and then enriches his distilled vision with skillful paint

handling

and careful orchestration of light and dark tones.

The

main

light source of the picture is a highly generalized projector, largely

without detail, that seems to shoot cartoonish rays of light from its

cannon-like

lens. The projector here has a metaphorical or symbolic function

and needs to be considered in terms of its mechanics. Projectors

typically

operate by shining light through a picture, typically a slide or film

frame.

Thus, projectors 1) project an image onto a wall or screen,

2)

shine light through or illuminate an image, and by so doing 3)

use

the power of their light to make an image enlarged and comprehensible

for

the viewer. While Van Laarâs projector produces raw light

without

the intermediate transparency of slide or film, several words or

concepts

in the description above are significant and meaningful for

interpretation.

For instance, the word illuminated may refer to not only a physical

phenomenon,

but also the production of a spiritual or intellectual awareness.

The concept of projection seems to deal with both the act of physically

enlarging an image through light and dramatically focusing on a

particular

isolated notion so that viewers pay extra attention to it.

Projecting

onto a wall or screen through illumination, therefore, seems to refer

rather

poetically to the art-making practice in general. Van

Laarâs painting

on the wall is a projection of ideas gained through illumination.

His personal experience with light, or The Light, is what he wishes to

communicate through his two dimensional creation displayed on the

gallery

wall.

This sense

of personal revelation is reinforced by the bareness of the stage that

serves as the setting or arena in which the pictorial action takes

place.

A stage is by nature not a private space; it is an open setting meant

to

present to viewers some significant action for both their entertainment

and edification. The generalized, nondescript character of the

stool

and projecting device ensures that nothing distracts from the gesture

or

activity taking place on center stage. Interestingly, what seems

to be this key gesture appears to be obscured or hidden by a suspended

sheet. That is, the human figure, so often the primary subject of

a work of art, is purposely hidden by the artist so that the viewer

pays

primary attention to what that figure is doing. Here is yet

another

example of certain elements or concerns subordinated in order for the

artist

to guide the viewerâs attention to the main theme of the

work. The

presence of hands and feet provides the viewer with evidence of a human

figure standing between the projector and sheet. Yet the shadow

and

the meaning of that shadow are more important than the personâs

identity;

witness, as further evidence of the shadowâs significance, the

legs in

the shadow straight and together, as opposed to the figureâs feet

spread

widely apart indicating a different pose. A precise and accurate

transcription of the cast shadow is less significant than the idea the

shadow pose expresses.

The

shadow

pose would clearly strike most viewers as mirroring the pose of the

crucified

Christ. While such a pose could be found in other places or

contexts,

the straight body with outstretched arms is so deeply embedded in

Western

consciousness that the association of this

body position to Christ is

immediate

and nearly without question. Van Laar in fact could have even

intended

a different meaning for his painting and the figureâs

gesture. However,

the frontal cross-shaped pose is so strong in its history of

associations

that viewers may automatically assume a Christian basis for the

picture.

Viewers, then, see the shadow not necessarily representing Jesus, but

more

referring to the divine nature of the crucified form.

The

shadow

is without interior detail. Thus, once again Van Laar directs

viewer

attention to the most significant elements within the work. The

shadow

is cast by a man (the shapes of the figureâs hands and the type

of shoes

seem to indicate that the figure is male), a point which seems to

relate

to both the humanity of Jesus and Christâs spirit residing in the

human

heart. Thus, the artist seems to be offering a dramatic revealing

of a Christian soul or essence, brought about by a climactic bathing in

powerful light. Earlier parallels with the terminology of art

making,

however, would lead one to expand on this Christian analysis. An

experience of the divine, in other words, is brought about by the

illuminating,

enlightening execution of the

creative act. Through

making

viewing and comprehending art, human beings are able to gain a sense of

God, the Holy Spirit, or secular Truth (although only a shadow picture

is possible; to fully comprehend or capture such splendor is beyond

human

capability). Van Laarâs stretched sheet is a metaphor for

his canvas;

the shadow silhouette is a metaphor for his artistic soul. Like

all

artists who feel the need to express the inexpressible through highly

personal

creative products, Van Laar manipulates his chosen images to

communicate

the idea that all works of art, faithfully and sincerely produced, are

manifestations of the artistâs spirit. The desire to

celebrate and

comprehend pure beauty and the quest to express oneâs admiration

and gratitude

for that beauty lead the artist down a path of humility. The act

of painting, the act of making art, therefore becomes an exercise in

devotion,

faith, and worship. Van Laar does not wish the viewer to stop at

an identification of Christ or the crucifixion. He wants the

viewer

to see that his honest work, his best effort, has led him to the point

where he feels himself closer to the glorious yet humble, human yet

divine,

beauty within himself. Just as the strong light projects his

image

on the sheet, so too might art project a clarifying light to enable

viewers

to discover within themselves a marvelous spiritual force.

© by Gregg Hertzlieb

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()