~DIANE LOCKWARD~

PAULA

BOHINCE: INCIDENT

AT THE EDGE OF BAYONET WOODS

Bohince deliberately leaves the narrative

incomplete,

a strategy that works well to

pique

and hold

our interest.

The motive is never more than

speculation.

The suspects remain merely suspects.

There

is no real solution to the crime. As our speaker

attempts to

reconstruct a story she does not fully know,

she moves back and

forth

between present and past,

affording us the pleasure of

finding clues

and reconstructing the story ourselves.

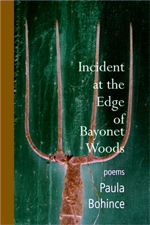

Paula Bohince’s Incident at the Edge of Bayonet Woods

is a stunning debut. Both a mystery and a lyric tour de force, the

collection immediately takes a choke hold on the reader’s attention and

never releases its grip. Poem by poem, Bohince unravels her dark story.

In Section I we learn

that the setting is a lonely rural farm located in the coal-mining

country of Pennsylvania. Primitive and shadowed by history, the farm is

characterized by mud, grime, cold winters, and poverty. The female

speaker, following her father’s grisly murder, returned to this farm

where she was raised, to live there and to claim her legacy of

loneliness. In the poems, she struggles to get to know her father and

to make sense of his life and death. Recalling the farm as it was years

ago, she says, “I taste the odor of straw and millet released into

fall, / the cursive of my father’s burning cigarette, / muslin curtain

parting.” Thus, the stage is prepared for the father’s entry and the

mystery’s unfolding.

While Section II introduces the suspected murderers

and suggests a motive, Bohince deliberately leaves the narrative

incomplete, a strategy that works well to pique and hold our interest.

The motive is never more than speculation. The suspects remain merely suspects. There

is no real solution to the crime. As our speaker attempts to

reconstruct a story she does not fully know, she moves back and forth

between present and past, affording us the pleasure of finding clues

and reconstructing the story ourselves. As she tries to remember events

from her childhood, she must acknowledge the fallibility of memory. In

“Landscape with Sheep and Deer,” she says, “I must have dreamt it,” and

she wonders, “. . . if there were deer, wouldn’t they have leapt over?”

Bohince subtly places us in that oddly delicious and ironic spot of

uncertainty. speculation. The suspects remain merely suspects. There

is no real solution to the crime. As our speaker attempts to

reconstruct a story she does not fully know, she moves back and forth

between present and past, affording us the pleasure of finding clues

and reconstructing the story ourselves. As she tries to remember events

from her childhood, she must acknowledge the fallibility of memory. In

“Landscape with Sheep and Deer,” she says, “I must have dreamt it,” and

she wonders, “. . . if there were deer, wouldn’t they have leapt over?”

Bohince subtly places us in that oddly delicious and ironic spot of

uncertainty.

Other smaller but seemingly important details,

personal ones that the speaker does know, are also omitted; thus, the

speaker herself remains somewhat a mystery. She has returned to the

farm, but never tells us where she has been or for how long. She never

makes reference to a mother. She tells us she is married, but provides

no information about her husband. She speaks of herself as “twice

married to the land,” and seems as much a bride to grief as to any man.

Bohince’s handling of atmosphere is masterful. While

the story is rife with the potential for passion, little is expressed.

In “Quarry” the daughter says it would be better “if I could quarrel

with these rocks, woo outrage the way / I woo sorrow. // There ought to

be a slow-forming fire somewhere, / not these pale mists, which are

moths, which are offerings of light / to the foiled landscape.” She

notes the “stubble of weeds waiting for some emotion to occupy it, /

though emptiness is its own kind of balm.” Ironically, this emptiness

serves to intensify the grimness of the story and to enhance the

feeling of overwhelming loneliness. As the daughter woos a sorrow she

cannot feel, we feel the damage that has been done to her.

The atmosphere is enhanced as Bohince reaches back

into the past, a strategy that has the effect of adding ghosts to the

story. In “Johnstown” the speaker recalls a young girl’s rape and how

the girl’s body was left frozen in ice. She recalls that the event

provoked her father to speak of the flood of 1889, how “the drowned

were found / as far west as the Ohio . . .” She concludes, “Here in

Johnstown, / we drift between the missing and the dead.” Bohince’s

inclusion of other voices also adds to the haunting. In “Spirits at the

Edge of Bayonet Woods” we hear the collective voice of the speaker’s

female ancestors describing “the poverty / and grime that kept us mired

here / for generations, as if we were sleeping / off a bender for one

hundred years.” We hear from these women, too, about the suicide of

Grace, who stripped, wept “beside the river’s illiterate banks,” then

was pulled into the water. The women pitied her. And they understood.

“Forgive her, Lord,” they ask, “for leaving this earth so early. / She

was terribly lonely.”

Bohince also charges the atmosphere with a complex

network of allusions, both biblical and classical. While the essential

story is utterly contemporary and realistic, these allusions add

timelessness and magnitude. Each of the three killers speaks in a

gospel poem: “The Gospel According to Lucas,” “The Gospel According to

Paul,” and “The Gospel According to John.” Ironically, although these

young men are called forth to testify, we cannot be sure they speak the

gospel truth. John refers to himself as “a snake in the grass . . ..”

Details about the father and his murder are revealed in “The Apostles”;

here, too, Bohince adds a touch of irony as the father referred to his

three laborers, the men who betrayed him for money, as his “apostles.”

In “Pond” we learn that the father’s “body lay / for three days before

its discovery . . ..” Then the idea of resurrection is implied in

“Adoration of the Easter Lamb” and in numerous references to lambs.

“Prayer,” the first poem in the collection, offers a

lovely ambiguity between The Father and the speaker’s father. This poem

also has the feel of a Greek invocation to the muse. While the biblical

allusions add the ideas of sin and the possibility of redemption, the

Greek underpinnings call forth the ideas of inherited curse and

inescapable fate. In “Oriole” there are three orioles; the third “is

wise, / the oracle / playing against his fate . . ..” The daughter’s

neighbor, Marie, has visions, though in “White Trumpets” it is

suggested that the visions may be drug-induced. In “Charity” we hear of

Marie’s father who “called her Golden

Dream / and fed her Quaaludes, / leaving her babbling on the

woods’ blank stage . . ..”

Another of Bohince’s poetic gifts is revealed in the

constellation of intertwined images of beauty and ugliness. In “Prayer”

the speaker addresses her Lord “beneath this raw milk sky, your vision

/ of silvery cream comprising daylight.” The beauty of this is in stark

contrast to the grotesqueness of one of the collection’s strongest

images—bones. In “Trespass” we learn that when the father was

paroled from prison after having served a three-year sentence for petty

theft, he returned home and took his daughter into a neighboring

pasture searching for bones to sell. The speaker recalls “the dreaming

gnats we awakened / discovering the lode of bones. // Collecting skull,

rib, sternum, spine, the dead . . ..” Similarly, in “Landscape with

Sheep and Deer” the daughter reveals her father’s love of

animals—“sheep of the earth, / the cloud-like sheep, and the

earth-toned deer / that belonged to the sky.” She evokes the beauty of

the field: “Radiant heather and tiny white tongues of clover, / soil

glittering with the misery of rain.” But here again we find “bones of a

field mouse, / horse flies spinning in the trough . . ..” It is

difficult to encounter such images and not think of Beelzebub, Lord of

the Flies.

While there is no solution to the crime, there is

for the speaker a kind of resolution achieved in the third and final

section of the collection. In “Watching Lightning Strike the Walnut,” a

poem full of metaphorical implication, the speaker sees in the struck

tree a metaphor for the effect her father’s murder has had on her: it

divided her into “before and after . . ..” With the tree smoking, she

stands on the porch, “electrified by loss.” And yet, as she reaches

into the past, she remembers a loving father and is able in “Toward

Happiness” to say of him, “I loved one person all my life.” Ultimately,

she acknowledges that beauty and ugliness reside side by side. In

“Charity,” the collection’s closing poem, she says, “But what the Book

/ omits, what the song, is how He allotted / for each gift one

brutality / for balance.” This resolution is impeccably achieved in the

way Bohince balances contrary images:

What I remember

is one sheep

who left her lamb in summer

to swim in the pond-turned-mud,

her legs filthy, curls

matted and ugly,

gnats strumming softly

It’s over, It’s over over lily

pads that broke

the surface, my hands

holding the rope’s crimped end

for hours.

And when I cry, I can hear her

still

crying in the loam, stranded,

dazzled by white flowers.

This collection’s chilling story is told beautifully by a gifted poet.

That it is told incompletely and dispassionately adds complexity and

irony. The reader is intrigued by the mystery, but because Bohince is a

poet and not a mystery writer, she wisely sends us off with unanswered

questions, leaving us haunted by the story, the characters, the

setting. And certainly by the poetry.

Incident at the Edge of

Bayonet Woods, Paula Bohince. Sarabande Books, 2008. ISBN:

9781932511628 $14.95

© by Diane Lockward

|

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()