Read This Next: Grace Biermann

I’m going to bend the rules a little bit today and recommend a story from the Christopher Center’s collection that you can read, watch, or both. This story is “Rebecca,” written by 20th century author Daphne du Maurier. The novel was published in 1938, and then adapted into a film that was released two years later, in 1940. Both the book and the movie are moody, pseudo-Gothic masterpieces.

“Rebecca” follows the story of a naive and friendless young woman who meets and soon marries a mysterious widower named Maxim de Winter. The newlyweds then return to his mansion, Manderley, on the southern coast of England. Manderley soon becomes all but a character in the novel, its presence by turns beautiful and frightening. And, speaking of frightening, the titular Rebecca is not the novel’s narrator, but the first Mrs. de Winter, who died under somewhat mysterious circumstances only a few years before the beginning of the novel. Rebecca herself haunts the story, especially since Manderley’s housekeeper, Mrs. Danvers, is still obsessed with her, an obsession that will eventually prove dangerous.

If this all sounds somewhat soapy and melodramatic, well, maybe it is, and the plot is crammed with one twist after another. But du Maurier is a top-notch writer, and her gorgeous prose and psychological insight definitely set this novel apart from most thrillers.

The film is also excellent. Directed by Alfred Hitchcock, and starring Joan Fontaine and Laurence Olivier, with a great supporting cast, it is a spectacular example of how to make a book-to-film adaptation. It’s also a beautiful movie, with black-and-white photography that adds to the haunting ambiguity of Manderley and its residents. And you don’t need to take my word for it: “Rebecca” won Academy Awards for Best Picture and Best Cinematography in 1941, and was nominated for nine more.

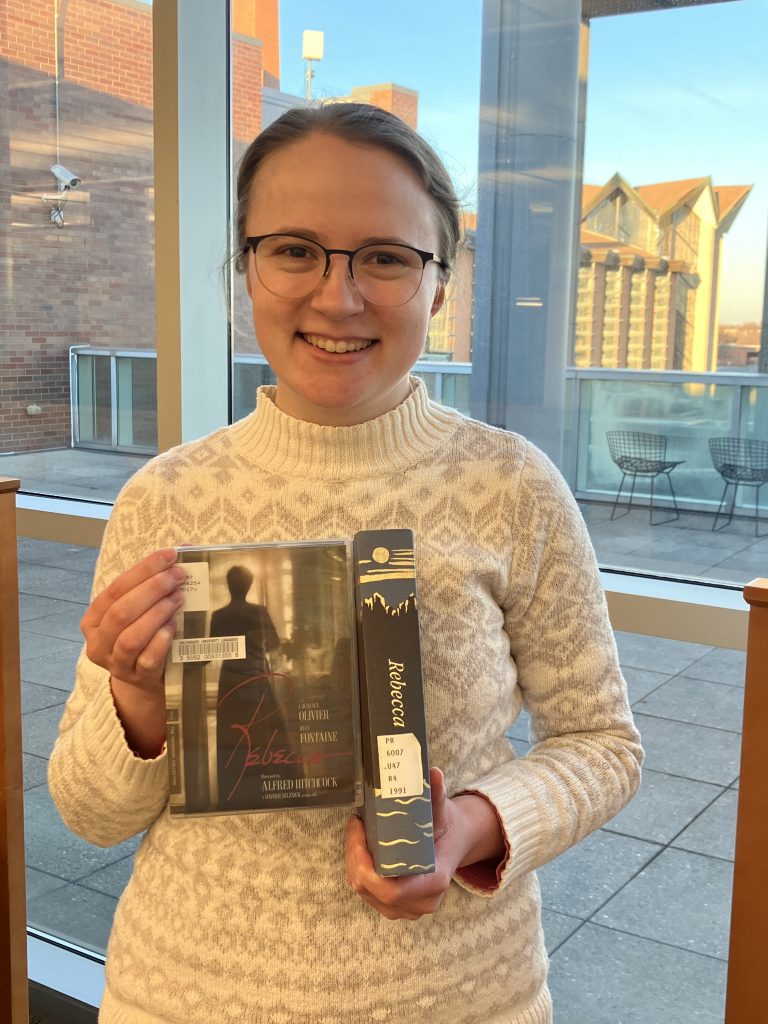

There’s also one more fun fact about this movie: while it’s a very faithful adaptation of the book, it does make one pretty significant change to the plot. This was not necessarily because the writers wanted to change the story, but because a change was necessary to make the film comply with the Hays Code, which had strict guidelines for what kinds of content could appear in films. If you want to know what that change was, come to the Christopher Center and check out the book, the movie, or both! The call number for the novel is PR6007.U47 R4 1991, while the film can be found in our DVD collection on the first floor of the library, shelved alphabetically.

I enjoyed both the book and the movie of “Rebecca,” but there are a few other titles in the collection that I’d love to recommend, as well. If romantic 1930s thrillers aren’t your speed, then check out “Till We Have Faces,” by C. S. Lewis (PR6023.E926 T54 2017); “Cry, the Beloved Country” by Alan Paton (PR9369.3.P37 C7 1995); “A River Runs Through It,” by Norman Maclean (PS3563.A317993 R58 1989); or “The Wednesday Wars,” by Gary D. Schmidt (PZ7.S3527 We 2007). And if you want to talk about any of them, swing by my office, CCLIR 265. I’m always happy to swap book recommendations!