Bias at the Plate: What Umpires Tell Us about Evaluators

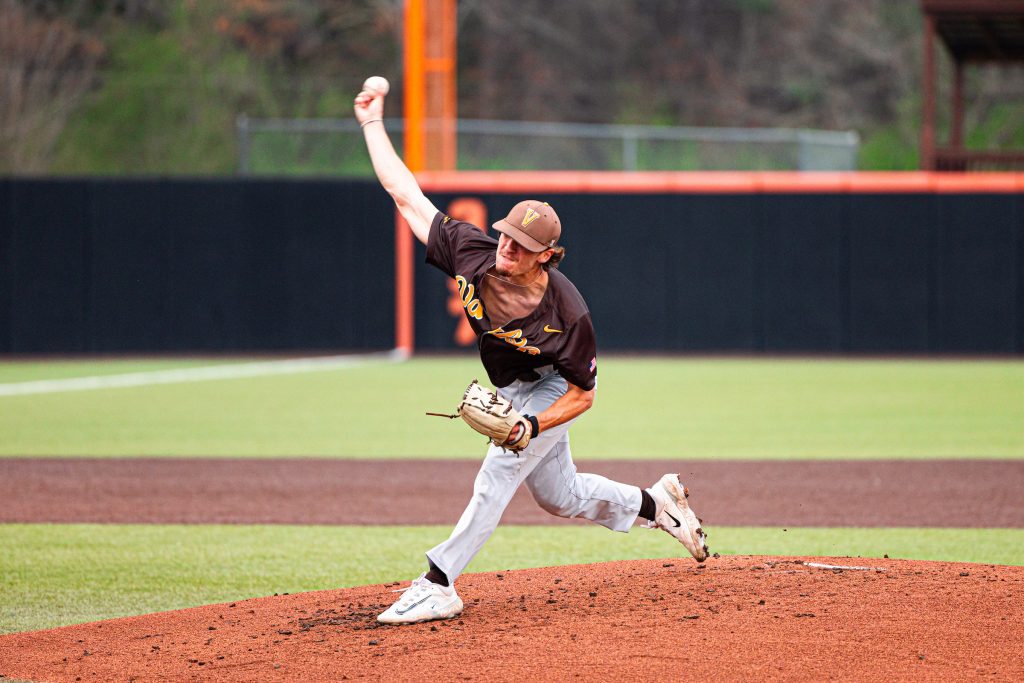

Baseball season is underway at Valparaiso University — as well as MLB spring training sites in Florida and Arizona — and one professor has used his love of the sport, combined with his passion for data-driven research and economic theory, to investigate an issue faced by most athletic events: home-team bias. Mike Hsu, assistant professor of economics — and Los Angeles native and Dodgers fan — wanted to find out if umpires are really favoring the home team during games and, if so, whether or not the issue was resolved with experience. His paper, “Umpire Home Bias in Major League Baseball,” was published by the Journal of Sports Economics in December of 2023.

Professor Hsu has been passionate about baseball since the 1990s and saw the game’s potential for research projects in academia.

“Baseball is rich with data,” Professor Hsu says. “There’s a lot more things we can prove, and there have been a lot of economics topics that can be answered using baseball-related data.”

The economics topic in question during this research was on the trust placed in those evaluating performances, how outside pressures can impact those evaluations, and what can be done when the bias definitively exists.

Professor Hsu’s work was not the first to put officials under the spotlight. The home-team bias phenomenon has been well-documented in the past in sports like soccer and basketball. However, Professor Hsu believes that baseball can, by the nature of its rules, offer unique insight into the phenomenon.

“I argue that, in many other sports, there is perhaps a lack of objective definition in play calls,” Professor Hsu says. “But in baseball, there is. The strike zone is objectively defined. Pitch location is something you can track. So you can compare the actual call to what should have, hypothetically, been the call based on the pitch location.”

Even with the advantage of greater objectivity, proving that the bias existed was no easy task. Professor Hsu looked through the pitching data of ten years of games, from the 2010 to 2019 seasons — more than 10,000 games in total and a mind-boggling number of individual pitches. With the data collected and the numbers crunched, Professor Hsu found that, on average, umpires were calling one to two questionable pitches in their favor per game, a tendency that was more pronounced when there were more home team fans in attendance.

“Even though the bias is not big, in terms of absolute magnitude, it’s still statistically significant,” Professor Hsu says.

The real surprise came when Professor Hsu looked at how experience impacted the tendency towards home team bias, or rather, how experience in dealing with the pressure of a home team audience failed to impact the tendency.

“You would think that a more experienced umpire would be less prone to the social pressure that favors one team over the other, but that doesn’t seem to be the case,” Professor Hsu says.

With this information, the question becomes one of what to do when the bias in what should be an objective evaluator seems insurmountable. If experience with performing under pressure does not mitigate the impact of that pressure, what can be done to ensure the integrity of the rules? According to Professor Hsu, it may be time for the evaluators themselves to undergo evaluation.

“You want to think hard about how to incentivize performance evaluators,” says Professor Hsu. “In baseball, that’s using machines rather than humans to call pitches. That’s the current trend.”

Whether machines take over the role of umpire or not, Professor Hsu will continue enjoying the game in the new season, even if his academic work in the sport has changed the way he watches certain parts.

“If the home team is at bat, I definitely pay a little more attention, especially with umpires who are known for not being accurate in their jobs,” Professor Hsu says.