Julie Kane: Review by Susan McLean

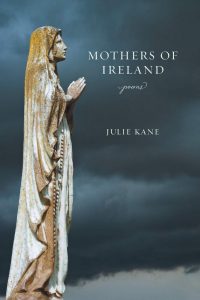

Julie Kane: Mothers of Ireland (Louisiana State University Press)

If I say this book is about life and death and family, you may well wonder how that makes it different from many other collections of poetry. Yet if I say this book examines family as an issue of life and death, I will be coming closer to what gives this collection its power. It is a heart-breaking, heart-mending examination of how the history of several generations of Julie Kane’s own Irish immigrant family left her feeling doomed, and how, slowly and with many losses along the way, she found her way out of alcoholism and the dead ends that took so many of her relations.

At the start of the book is a list of Kane’s eight great-great-grandmothers, four great-grandmothers, two grandmothers, and mother, all of them of Irish extraction. Some of the poems are about how tragedies of Irish history left their mark on these women: how the Potato Famine led to starvation and the arson that burned one woman’s house on Christmas Eve in 1846; how emigration, drudgery, and alcoholism marred the lives of many of the others; how a cousin who remained in Ireland spied for the IRA after her brother was shot and killed by British soldiers. But some of the poems are about how, as women, their lives were warped by lack of options; by shame at poverty, discrimination against Irish Catholics, a mother’s adultery with a priest; by emotional coldness or alcohol abuse as a protection against being hurt.

In some hands, these tragedies would be milked for sensationalism or pity, but Kane’s matter-of-fact handling of even the most shocking turns of events commands respect. One key element of this control is her frequent use of poetic form, and especially forms of repetition, both to emphasize the cyclical nature of the families’ problems and addictions, and to gain enough distance to cope with the explosive material. One villanelle starts out “What kind of mother calls her daughter ‘whore’”(“Whore”). Another starts “I used to have a scream stuck in my throat” (“The Scream”). Kane’s repeating forms—such as ghazals, pantoums, sestinas, and villanelles—are loose enough to avoid the lack of surprise that strict repetition can lead to; their flexibility allows a narrative arc that readers don’t see coming. However, Kane also keeps her approach varied, with slant-rhymed sonnets, haiku, prose poems, couplets, and even free verse.

What really makes this collection one of the most impressive I have read are the moments in which a phrase perfectly ties together threads that I did not think were connected. In the series of four villanelles called “Family Dramas,” I recognized the names in each of the first three as being from Kane’s grandparents on both sides and her parents. But when I reached the fourth, titled “Act Four: The Cavan-Tyrones,” it took me a moment to realize that those names were not from Kane’s family, but from Eugene O’Neill’s Long Day’s Journey into Night, and the connection between the fights, addictions, and hopelessness in her story and in his fell into place like the keystone of an arch. “Thorn-Hedge Villanelle” starts “Is getting sober like the act it takes / to free a kingdom from a magic spell?” and follows the Sleeping Beauty metaphor until the end: “four in your generation spared the hell / that took your elders as a thorn-hedge takes / a kingdom where all die before they wake.” The subtle echo of the childhood prayer’s line, “if I die before I wake,” is both a reminder of the toll of addiction and part of the theme of the last section, a nonbeliever’s search for something to lean on. Her answer is hinted at in “To Tame a Feral Cat,” in which the practical advice on patiently winning the animal’s trust can be applied both to the speaker’s wary self and to the higher power or sense of purpose that she is cautiously courting.

In the third section, “The Cruel Mother,” Kane tackles her most explosive subject: coming to terms with an abortion and its aftermath. In this section, the connections tingle like live wires. “You Were So Good” is addressed to the embryo and ends

You were so good, you must have been a girl

That one trimester that I carried you:

Trusting innately if you made no fuss,

Just kept your head down and were good enough,

I wouldn’t let them cut you out like cancer.

I didn’t ask your sex. I knew the answer.

In the sonnet “His Dream,” the father of the unexpected pregnancy, driving the speaker to the women’s clinic, tells her “The night before, he dreamed about a mouse / clinging to a vacuum cleaner wand.” The nightmarish quality of that image is indelible. In the last poem of that section, “Tunnel of Light,” Kane imagines meeting her own terrible mother and her unborn child in the afterlife: “I don’t fear dying, but I fear those two. / O holy mother, help us to forgive / Those who killed us and those who let us live.”

Readers who are allergic to villanelles and other repeating poetic forms will probably not be won over by this book, in which they are ubiquitous and part of the very structure of it. But those who crave that shiver of recognition when two unrelated events chime in unexpected ways, like a spiderweb that vibrates in every part when any thread of it is touched, will find this book hard to forget.

Susan McLean, a professor emerita of English at Southwest Minnesota State University, is the author of The Best Disguise and The Whetstone Misses the Knife, and the translator of Martial’s Selected Epigrams. Her poems and translations of poetry have appeared in Subtropics, Hunger Mountain, Able Muse, Literary Imagination, and elsewhere.