William Walsh: Review by Clayton Ramsey

William Walsh: Fly Fishing in Times Square (Cervena Barva Press)

If the purpose of art is pure mimesis, then 2020 would have only produced horror novels, heavy metal symphonies, and chaotic canvas splashes. But thankfully the Muses are not as cruel as the Fates. In the midst of the ongoing tragedy of last year, William Walsh produced a lovely collection of poems with the fanciful title, “Fly Fishing in Times Square.” It is a welcome respite from the angst of these days.

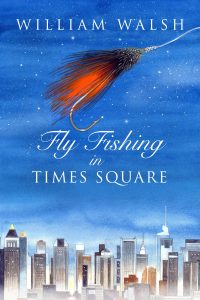

The central image of the cover graphically captures the composite idea of the collection, a visual oxymoron that transcends the apparent contradiction to anticipate a compelling thematic unity. A fly-fishing lure, a crimson feather hiding the shaft of the hook, suspended as though just cast, and a modern skyline, a fraction of the buildings in Manhattan at twilight, office lights mirroring the spangled sky. The first conjures associations with Big Sky landscapes, rolling hills, meandering rivers, Nature. The second, just the opposite: jostling humanity on crowded sidewalks, car horns blaring, Civilization. The reader is meant to see the contrast, to feel the difference, to smell the meadow air and taste the exhaust, a dissonance for their senses. It is not quaint and whimsical, however, but nettlesome and disorienting.

But it is this initial dissimilarity, this visual contradiction, that prepares the reader for the collection of poems contained in this slender volume. With this incongruity, the reader is immediately looking for a resolution. Fly-fishing and cityscapes are emblems of two very different worlds, the reader thinks. One does not, one cannot, fly fish in Times Square, the epicenter of modern commercialism, where concrete and asphalt have long since covered over streams brimming with fish. Where is the point of contact, the reader is compelled to ask. What does one have to do with the other? The poet may just as well have entitled his collection “Quilting in Silicon Valley.” Perhaps the image represents two chronological ages, two psychological states, two geographies. Or just maybe they’re not meant to represent mutually exclusive experiences at all. Maybe, in the brilliance of the poetic mind, as the reader wrestles with the verses that follow, the reader begins to see congruence. Perhaps this stark incompatibility lies at the center of his compositional strategy, beginning the reader’s journey with a puzzle that needs solving, a logical fracture that requires healing, moving her from the fragmentation of images that don’t match, through poetry, to a place in which they do.

The reader turns the cover unsettled. The table of contents does nothing to elucidate the disjunction. The poems are arranged in four sections: “We Don’t Know How To Behave,” “Her Beauty Obscures All Reason,” “The Death of Baseball,” and “Memory Is My Homeland.” Instead of an epistemic guide to the work, a framework for interpretation of the problem readers carry with them into the collection, they find only more pieces, not an architecture of integration. Behavior, beauty, baseball (for goodness sake), and memory—four pillars holding up a structure that cannot yet be named. The hermeneutical dilemma deepens. The theme is not apparent, if the reader hopes to find one at all.

And then, in the first offering, in the middle of Uncle Harvey’s liberation of dry cleaning bags filled with gas, readers get the first hint of what they’ve stumbled into: “What happens / when imagination confronts the universe?” (3). This was the preoccupation of ancient philosophers, the relation of mind and matter, that has endured into our age. Their question becomes our own. Here Walsh exposes one of the theoretical underpinnings of his work with a perennial question, and the reader quickly sees, even from the first verses, that she is not just dealing with a poem about an eccentric relative; eyes begin to widen as the reader is reminded that “there’s no controlling the world’s divine mysteries” (3).

Walsh has a particular gift for joining an evocative lyricism with blank verse narrative. His poems are little stories, at first glance almost polished charms on a bracelet, reminders of people and events collected as cherished mementoes from an earlier life. His style and substance interlock such that as the reader is dropped in scenes–encountering Secretariat on a family trip, playing with a Lionel train bought by the author’s grandfather after the war, using a duffel bag of his father’s, tempting fate with his friend Cosmo and the Flames of Death, teetering on a church roof—she begins to see connections. And perspective shifts as the reader realizes these memories are not straightforward images, much like the cover. By the time the reader reaches the end of the first section, she will have seen things filtered through a brother’s memory, artifacts as means of escape, excitements untethered from reality, visions of a “jeweled paradise” (13) dreamt in the past and longed for in future perfection, memory captured in art, and the ache of words unsaid. The section is capped with the eponymous poem and the author finding himself in Manhattan in a “search for a miracle to smooth the creases, / to pull something from the depths of anonymity,” (16) whereas, he confesses, “all I can think about is a trout stream” (16) and an escape from the press of humanity in the quintessential urban environment. These are memories, but with a nuance and depth that will take the rest of the collection to unwind.

Memories of action, however misguided, of daredevils and hunting trips, turn to memories of love, entangled as they tend to be in the mind of every man, a complicating factor mediated by beauty that only seems to agitate the mind and inhibit its rational function. The sweetest and most poignant of recollections are those of first kisses and slow dances at senior prom. But as with the early poems, Walsh does not reach for the expected in the second section. The first exploration of his stated theme is about his mother and aunt at Lakewood Beach, pretending to be movie stars, not ready to grow up, the scene of the bright day captured in a photograph. And staring at the photo, the author only wants to reengineer the memory to give her life a different outcome. He knew how it would unfold and he wanted to spare her the suffering. “If only I had given her a chance to reconsider / the options beyond good looks/and a sparkling smile.” (19). Here the memory is fluid, the arc of her life mutable. And that is his longing: to bestow an alternate history on the first beauty that emerged in his life, his mother, before she faced the inevitability of his friend, Jonathan’s, mother’s fate and memory is memorialized and remembering is a rite of mourning.

Memory winds its way through every conceptualization of beauty and its melancholy reminder in this section. There is the author’s treatment as a “homeless mutt” (23) by his girlfriend’s parents because he was a poet and thus deemed not good enough for their daughter. “You and I could have been happy together” (23), he laments, the pain losing its sting but not its ache over the years. Sensory triggers stir many of the memories, whether it’s a Jenna Wakeman song, country ballads on a road trip from Nashville to Lubbock, the smell and aftertaste of a fine Bordeaux, or a “wave of nostalgia” (32) coming from a jukebox. Here memory is a platonic ideal worshiped in a crush, a mausoleum for the burial of a lover, a standard for the measurement of a life, a landscape outside a diner, a non-monetizable, elusive search for “an answer / for the cruel child rolled up / inside” (25). This longing for beauty and the existential fulfillment the reader hopes to find when she surrenders to it, the rehearsal of the serial pursuit the reader sees in his history of love affairs, reveals the absolutely arbitrary and uncertain nature of the quest, in the words of every aging lover: “It’s a craps game, / this thing called love” (32). This record of love and loss, called to mind in retrospect, uncovers the role of recalled history in the tangle of emotions, longing, and vulnerability known by all who have loved. Beyond flowers and kisses and dopamine bursts, there is the backdrop of past hurts, emotional scars, and disillusionment, and memory is the storehouse of this record. Beauty is the hook, but it is memory that is the wise counsel and historian in the sweet transaction when time collapses onto a blessed present, nevertheless shadowed by an imperfect past but anticipating a perfect future.

And from the ethereal heights of cherished childhood memories and the eternal search for lasting love and beauty, the reader slams into the third division of the collection and the death of baseball. However beloved the pastime may be for Americans, it is still an oddly jarring transition from the topics of the first half of the poems. In nine sections, the author tells the utterly surprising story of Martin Turner, the cranky old man in the young author’s neighborhood who was in the habit of calling the cops on him and his friend when they were too loud, or played baseball in the street, or smoked pot. “Shawn and I were like lemmings, / just looking / for any cliff to jump off” (37). When old man Turner was on a three-week vacation in Europe to revisit his own memories of the war, the boys discovered their own “new world / of revenge” (38). With an act that was as creative as it was impish, the boys fled the scene, chasing girls elsewhere, “each girl desperate / for some memories of her own to bottle-up / and cast into any ocean of acceptance, memories / to float back to their rocky shore one day / with fondness” (40). By the time their mischief was complete, the mementoes of Turner’s history were obliterated: “whatever / wasn’t held tight in the vice of his mind / filled the dumpsters” (41). Memory thus erased, everything changed. The baseball games of childhood ended. The author’s buddy Shawn moved away to become “just a memory / for me, a pocket charm / to ride into adulthood, or perhaps I was the memory” (42). In this micro-history, complete with its own story arc, it is memory that holds the social fabric together, memory that fuels a desire for revenge, and memory, when annihilated, that causes the actors in this drama to spin off in different directions. The network of relationships is represented by baseball and the movement of the game from its enactment to its death mirrors the lifespan of the neighborhood. For the author, baseball is not just “peanuts and Cracker Jacks”; it is a symbol of community. And its demise, held in memory, is ultimately a representation of lost relationships.

In the fourth division, the themes that flowed in the substrata of the first three emerge on the textual surface; the archaeology of recollection in the excavation of “memories dredged from the muck / of childhood” (51) becomes explicit. With his confession, “I want to live in a small town like Lakewood” (48), he is idealizing the past in the wish fulfillment of domestic life and family relationships. Here in the past there is pure enjoyment and perfection, the longing for an ideal past in small town America that exposes the shortcomings of the present and informs the possibilities of a utopian future. With the dismantling of a cedar playhouse, memory is seen as threat and animal energy. In memorial verse for the loss of a friend, memory becomes submersible pain, where “everything’s a metaphor / for what pins my sadness below the surface” (51), concluding, “this woodsman searches for holiness / in every lonely thing” (52). Memory is the stuff of vision quests as the author “dreamed the dream of unclaimed dreams, lost by others over time” (54). It is the material of place, both mental and physical, scooped up in the stolen sod and dirt of past homes, and incarnated in the creatures of the Okefenokee Swamp. It is the shade of a grandfather in a dark room and a reservoir of regret for a father who had an “impressive resume of blown opportunities” (59) as a baseball player and a man. Memory is the space the reader returns to often for sustenance, like chipmunks swimming to an island for nuts and then returning home with cheeks full, the residue of lived experience held in an afterlife, or “what’s left behind / when the adventure ends” (62). It is an inheritance, a legacy, a gift.

Walsh names this final section “Memory is my homeland,” a pied-à-terre in his passage through the world, a source of identity, proof of citizenship in the fraternity of humanity. But what is such memory? A compendium of images associated with past experience? Such a definition is simplistic and unsatisfying. Memory, he reminds the reader, is not like a photo album, crisp snapshots of the past fixed and filed away neatly in the hippocampus. They are forgotten, misremembered, conflated, edited, altered, invented, partially recalled. In fact, Walsh does not present a facile picture of memory; he insinuates himself in the intersection of a philosophical triad of mind, world, and time, and explores what occurs at the point of contact with language that is fundamental, evocative, and nostalgic. As he encouraged the reader to ask in the first poem, what does happen when a mind confronts the world? Drawing from images of past experience, transformed by time, twisted, broken, burnished, he leads the reader to imagine a future that threatens to narrow by solipsism, expand by ego, quake with anxiety, and shine with Panglossian optimism. The present should be the intersection, an immediate confrontation of mind and reality, but the reader cannot escape the intrusion of the shadows of the past and the possibilities of the future, both crowding out and modifying her direct encounter with the world. This triangle of interaction is dynamic and mutually influential. And Walsh does a stunning job helping the reader navigate between these elements.

Just as the reader reaches the last line, just as the reader’s mind searches for the solution to that paradox that confronted her on the cover, she sees how one image interconverts and folds into the other. The reader remembers from the shadows of history that the Canarse and the Wecquaesgeek indigenous tribes hunted and fished in the land now covered with Manhattan skyscrapers. The reader sees that geography links fishing and buildings, past and present, Nature and Civilization. These are not the symbols of two worlds the reader thought them to be when she picked up the book. These are the same world at different moments, an interconnection joined by the cables of time and the threads of memory. There is a connection, a nexus, that binds both. And it is in moving from this tension to this convergence where we find the magic of Walsh’s verse. In a year in which apocalyptic crises such as pandemics, wildfires, hurricanes, murder hornets, misbehavior in high places, record unemployment, urban unrest, and any number of other catastrophes the reader may imagine a demented deity to have concocted in a masochistic moment, the reader has no problem coming to these poems broken, carrying the fragments of a splintered life.

Walsh meets his readers with an image that exposes the pieces that don’t match and through his poetry helps them to look for and finally accept a sort of wholeness in the images, in the collection, and in the reader by the end. The lure and the skyline are his iatrotropic stimulus, the condition that causes his readers to seek treatment, and it is what follows, the gracious art of his poetry, that helps readers see reconciliation, not just in the images, but in themselves and their world. Hamlet laments, “The time is out of joint; O curs’d spite, / That ever I was born to set it right.” (I.v.188-189). While Walsh cannot possibly heal our disjointed world alone, he does his best to nudge his readers along the way, to picture peace and simplicity and beauty, to hold two different images in the palm of his hand, and show them with his craft that a better world, a purer world, might yet be known.

Clayton Ramsey has been published in The Writer, Chattahoochee Review, Blue Mountain Review, and other journals. He published Viral Literature: Alone Together in Georgia, an anthology prompted by the pandemic that features the work of 32 of the best storytellers and poets in Georgia. Ramsey is the director of the Townsend Prize for Fiction.