Susan Rich: Review by Deborah Bacharach

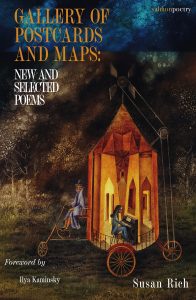

Susan Rich, Gallery of Postcards and Maps: New and Selected Poems (Salmon Poetry)

With a robust section of new poems and excerpts from her four previous books, the poems in Susan Rich’s Gallery of Postcards and Maps: New and Selected Poems mesh as well as surprise. Over the 22 years of these publications, a strong Jewish woman travels the world, and delves into art, self, and love. Rich brings “a suitcase of longings and laughter / that somersaults its way across the country” (“Song at the End of the Mind”) as she looks at the world with wonder, a place of alchemy.

Her first two books The Cartographer’s Tongue / Poems of the World (2000) and Cures Include Travel (2006) put a strong focus on travel, and the poems she’s picked for this collection take us to Niger, Palestine, Bosnia, Haiti, as well as the AIDS epidemic—places in the midst of conflict. The speaker is both self-aware and eager to know herself. In “The Filigree of the Familiar” she asks:

Do I leave to take a stand?

Or circle around the globe,

passport in-hand to get away from the incessant

no-win scenes, the frantic filigree of the familiar

pressing like dead dreams inside my head?

Perhaps the urge to travel is political—to make the world a more equitable place. Rich worked for Amnesty International and as a human rights trainer, but she also recognizes the urge to figure out who she is and where she belongs. In one of the new poems, “How to Travel in the Middle Period,” she writes:

And so you’ve learned to travel

through multiple waters and sky—

in the glide and drift of it—

like tree goats that forage,

then build their lives mid-air—

knowing yes! as the one chosen thing.

I’m not a big traveler, but once I imagine myself as a goat in mid-air, I too want to say yes.

As she travels, Rich is aware of her positioning as an outsider. In “Whatever Happens to the Bodies…” she asks:

Whatever happened to the bodies without names?

Whatever became of people cannibalized, drowned, depraved?

Whatever moves us eventually moves away.

The speaker acknowledges she cannot tell the full story, but she also does not shy away from showing what she sees, telling the stories she can.

Rich has a great talent to take what is outside us and make it personal. She often does this with ekphrastic poetry. She explores art from so many perspectives: the relationship the artist and model might have had, the relationship of artist to her husband, of art to students. In considering the lost art of withdrawing red velvet curtains, she captures the physicality, the sensualness: “How a person’s hands had to be constant / eagerly holding down, arranging / one movement over the other / in a meditation that involved / the whole body” (“The Lost”). We get to take this experience inside us.

I particularly like Rich’s new series of self-portraits. Partially an acknowledgement of “the different selves” the speaker carries, including her father’s face in her own, the technique lets us see the speaker from many different perspectives. In “Self Portrait as Leonora Carrington Painting,” the speaker is confident and defiant. Rich uses wonderful verbs to show the active purposeful engaged speaker taking control of their life:

Good-bye

to the asparagus of self-doubt, the onionskin envelope

of the lonely. Instead, let this hangover open

into uncharted happiness, let the sweetness be dangerous.

Unfasten the windows from their frames, take off

the rooftop from the triple decker house—join the hyena,

the horse, and the girl. Offer them wings.

First this speaker will “Unfasten,” “take off,” from what she doesn’t want, then not just “join” the wild world she does want but move others a step further by offering wings. She’s not just in control of her destiny but a helper to others.

In “Self Portrait as Gustav Courbet,” phrases like “Just outside the frame Courbet observes” deftly guide into the realm of the surreal. Rich then provides three concrete images of what she imagines outside that frame:

a child

languishing in a cage along the border—

like a zoo animal badly neglected; he sees a man

left to bleed out on a St. Louis downtown street;

witnesses a woman at home, killed by Seattle police.

Rich allows herself to range over time and place to find the images that match the despair she sees in Courbet’s eyes. There is a delicious tension between knowing these images are not real for Courbet the painter but are for us the readers.

Surrealism to confront despair, but also to wake us up to the ridiculous. I found myself laughing out loud to lines like “The house doesn’t like its ears. / It doesn’t like to listen to Madonna or Frank Sinatra” (“What If a House”) and “refurbished husbands are not a commerce to trade in” (“If My Life Talked Back to Me, It Would Say”). Particularly in these new poems with titles like “What I Learned from Bewitched” and “Vegetarian vampires walk into a bar,” Rich embraces humor even as she addresses devastating questions like “Perhaps we’ve arrived too late to save the world’s / gardens.”

But in Rich’s work, we are not too late. Her work focuses on that magical transition of the ordinary into the fantastic and valuable. How do I know? She titled one book Cloud Pharmacy (2014) and another The Alchemist’s Kitchen (2010), both places of magical transformation. And, a variation of the word alchemy appears eight times in this gallery. This is not on accident. It’s like Rich has given us a secret treasure to find.

Rich guides us see with wonder, even if it is the moment before a loved one’s death. In “Not a Prayer,” she zooms the camera in and slowly pans over a scene, revealing what we might have missed, “The table in the vestibule, / oak chair, and lavender / blue bowl, show themselves to be honey, butter, mustard seed.” We are offered not just the surface beauty of these objects, the strong flavors and colors, but the sustenance they hold. I feel my senses suffused. But the wonder of it all does not stay out there. The speaker says:

And I take what is shimmering

into my body

stand still, living still, for the first time all day.

I wait for the sunlight to speak,

to remind me how

transformation happens

regularly as dusk enraptures day—

This is a moment of alchemy where day changes to night, life to death, and wonder “shimmering / into my body.” Rich reminds us that wonder and alchemy are always here for us.

Deborah Bacharach is the author of Shake and Tremor (Grayson Books, 2021) and After I Stop Lying (Cherry Grove Collections, 2015). Her work has been published in The Antigonish Review, Cimarron Review, New Letters and Poet Lore among many others.