Eric Nelson: Review by Kathy Nelson

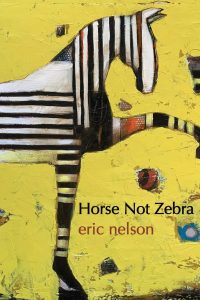

Eric Nelson, Horse Not Zebra (Terrapin Books)

Tension is the prominent aspect of Nelson’s collection. The dedication (“for my family especially the newest member Lowell Sinclair Cartright-Nelson”) suggests hope for the future, perhaps a rosy welcome for a child. But the book is full of grief: grief for the end of the natural world, for the disasters humans have wreaked upon the earth, for the absence of epiphanies.

Individual poems express the tension between the mundane and the apocalyptic, as in “Soap Spell,” which begins

Gather your soap

Bring out your soap

Scented and unscented

Dish and laundry

and ends

Stare fear in the eye and call

On the waters and winds to forgive

And cleanse us once and for all.

Other poems, such as “Gold,” about a gold mylar balloon hanging in a tree, highlight the tension between the light-hearted and the menacing. Here, the speaker speculates that a squirrel

…unfurled the balloon, sunny flag

of its disposition, then curled up to sleep

beneath the winter sky, where a hawk

floats in widening circles waiting

for something to catch its eye.

Still others, like “By Campfire,” which with its conversational tone enumerates the many ways, post-apocalypse, the speaker would be inadequate to help with the many tasks of survival,

… And the combustion engine—

the places it took us! But with a gun

to my head I couldn’t build one. Or the gun,

either, which may be the upside.

point to the tension between the humorous and the catastrophic. And yet, as a counterpoint to the anticipation of apocalypse, or as a moment of relief from the tension, the title poem itself reminds us not to panic.

When med students are learning

how to diagnose symptoms, they’re told

think horse, not zebra—the common, not the exotic.

Or if your love is over an hour late

for dinner and hasn’t called to explain, think

gridlock, not head-on; dead zone, not dead.

Weaving through these poems anticipating apocalypse, there are certain threads that appear and reappear: the many poems about the black bears that wander the poet’s neighborhood, the motif of the morning walks with the dog, mulch and the garden, the beloved grandson. These elements of everyday life ground the lament of the collection in an actual lived life. This speaker is a seeker in his day-to-day life, (“I wanted a seeker returning / from wandering, answer in hand,” from “Clearing the Air”), but a disappointed one (“No epiphany in sight, no holy whispers in the canopy”). He observes the bear, the dog, the sea glass Buddha in the woods as he looks for meaning, and it is in the depth of the observation itself that meaning lies.

Also running through the collection, beginning especially in part 3, are poems of personal memory. These memories shed light on American racism, which we learn in “Expecting Lowell” is relevant to the birth of the grandson. Sometimes, as in “Biography of My Name,” they reveal the blending of dissimilar families, also relevant to the child’s birth. It is in remembering his mother (“Scouts”) that the speaker finds his most hopeful voice: the dead are “Scouts, call us scouts…the ones who go ahead // to make sure the trail is clear.”

Regarding the craft elements of the poems in Horse Not Zebra, several are noteworthy. The diction is more ordinary than elevated, but music arises from the everyday language by means of repetition, as in “Almost Enough,” where “Or…Or…Or…” shifts to “almost…almost…almost,” the rhythm of the repetition escalating as the poem reaches its hard-hitting ending. There are poems with obvious rhymes (“Soap Spell”) and other poems with more subtle rhymes (“Switchback”). The emotional landscape of the poem is sometimes revealed through shifting vowel sounds, as in “Mulch”: long o sounds (smoke…slopes…smoke) morphing to luscious oo sounds (move…scoop…cooling) then back to long o sounds (row…porous cargo).

Two poems stand out for their imagery. In the opening poem, “Clearing the Air,” the scene in the woods is described using the vocabulary of church and religion (witness, communion, eternity, arches, scrolling, illuminated script) so that the reverence the speaker feels is made plain. Similarly, in “Washing Dishes at the Arsenal,” the dishwashing machine is described in terms of the vocabulary of artillery (pulled, pulled, loaded, shoved, blast, unpacked, stacked, explosion), revealing the speaker’s ambivalence toward his military job.

There are also quite a few exceptional line and stanza breaks: at the penultimate “almost” in “Almost Enough,”

There’s almost enough of us to wipe oil from a thousand gulls

before they suffocate, almost enough to drag dolphins back

into water deep enough for them to dive away from us, almost

and after “birthday” at the end of the first Jesus-referring stanza of “Twelfth Night” (“on the twelfth night / after the miraculous birth, the night of the birthday / of Stephanie”). These breaks intensify the emotional content, or they surprise and delight.

I have several favorite poems from this collection. “Expecting Lowell” beautifully invokes both the Preamble to the US Constitution (“more perfect union”) and, in its ending “I see you breathing” the last words of Eric Garner (“I can’t breathe”). By means of both of these references, the poem reaches toward the ideals of the country as well as its sordid history, and it does so with subtlety. I also admire “Not Here Not Here” for the way it juxtaposes two different scenes without explanation or transition, so that the reader feels compelled to find the meaning in that juxtaposition, to discover a sense of alienation that reaches both into the social world and the natural world. I admire “Scouts” for its remembrance of a beloved mother delivered without a shred of sentimentality and for its hopefulness about the role the dead play in our lives (and deaths). And “Blind Mover,” with its revealing self-correction mid-poem (“I wouldn’t have feared him—feared for him / I meant to say”) touches me deeply, compelling me to confront my own complicated prejudice and compassion. This collection, which juxtaposes new life with apocalypse, is full of such emotionally provocative moments. I find the collection very moving.

Kathy Nelson, was a 2019 recipient of the James Dickey Prize (Five Points, A Journal of Literature and Art). In addition to her two chapbooks, Cattails and Whose Names Have Slipped Away, her work has appeared or is forthcoming in The Cortland Review, LEON Literary Journal, New Ohio Review, Tar River Poetry, Twelve Mile Journal, Valparaiso Poetry Review, and elsewhere. [She is not related to Eric Nelson.]