Landscapist

The rising sun is heralded by colors most gorgeous and pleasing. The watching and expectant clouds, which are about his coming path say with tones of every hue to one another, “He comes,” and they shout down to us in orange and crimson “He comes.”

Things that Cost us Nothing, Junius R. Sloan, Winter of 1859, Sloan Archives, Brauer Museum of Art

Life as a Landscapist

For nineteenth century Americans, a vast, unspoiled continent, both spectacular and commonplace, was being revealed as the American homeland. Until the Civil War at least, most American landscape painters celebrated this homeland vision as a symbol of America and of God’s goodness. Junius Sloan was one of those artists; he came late and stayed long at this task. For him, painting the beauty of Divine order in untouched and pastoral landscapes had long been akin to an act of worship. Junius painted ‘beauty for the joy of it.

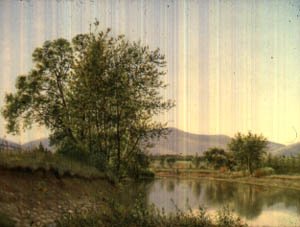

Junius R. Sloan

Catskill Creek–near Leeds, 1869

Oil on canvas, 13 x 23 in.

Percy H. Sloan Bequest

Brauer Museum of Art, 1953.1.135

Early Landscapes

“To see clearly is poetry, prophecy and religion–all in one.”

-John Ruskin

For Junius, painting the beauty of Divine order evident to him in untouched and pastoral landscapes had long been an act of worship and a career goal. For instruction, in August 1857 in Princeton, Illinois, Junius bought the just published book, Elements of Drawing by the British critic and landscapist, John Ruskin. Its Exercise VI inspired, seemingly, Junius’ scrupulous drawing of trunk and boughs in his 1860 Tree Study. Further, Junius’ July 2, 1861 sketch of an elm tree reflects Ruskin’s advice to give close observation to the “decisive” forms of massed leaves and to their “softness of surface.” In the mid-sixties, in his home base of Chicago, Junius exhibited such paintings as Small Falls and Esopus Creek.

For years Junius’ early landscapes seem obsessed with picturing Ruskinian truths of particular facts. Then, in 1865, during a summer of field sketching in the East, Junius’ landscapes abruptly softened for what Ruskin called “general truths of tone, atmosphere and space.” Such truths are evident in Junius’ 1866 prairie landscapes with their emphasis on the sky and clouds from sunrise to sunset.

Junius R. Sloan

Catskill Creek–near Leeds, 1869

Oil on canvas, 13 x 23 in.

Percy H. Sloan Bequest

Brauer Museum of Art, 1953.1.135

Professional Success

“The Catskills, a by-passed bastion of wild beauty close by the most civilized centers of the eastern coast [had become] a…leading motif of the American romantic movement.”

-Roland Van Zandt, The Catskill Mountain House, Rutgers University Press, 1966

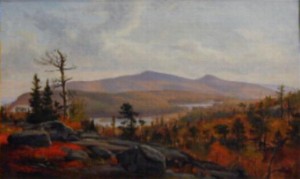

Encouraged by his three years in Chicago as a novice landscapist, Sloan, in June 1867, sought professional excellence, not by a grand tour of Europe or an exploration of the far west, but by a five-year pilgrimage of self-education at classic landscape scenes in the Hudson River Valley, including the Catskill Mountains, Lake George, and Vermont. By late August, settled on the Dietrich farm near Palenville, Junius began pencil and oil field sketches of Lake George and of views centered on the Catskill Mountain House resort hotel, views celebrated by painters Thomas Cole and Jasper Cropsey, and by writers James Fenimore Cooper and William Cullen Bryant. In 1868, R.E. Moore, Junius’ Chicago dealer, sold an exhibition-sized composition, View of Lake George, to Lake George native and prominent Chicago business leader C.R. Larabee for $300, and Ticonderoga to George M. Pullman, thirty-six, founder in 1867 of the Pullman Palalce Car Company, for $200.

Junius R. Sloan

Road to Lake, Rogers Park, Chicago

Watercolor, 7-5/16 x 11-1/4 in.

Brauer Museum of Art, 53.1.333

Late Landscapes

When Junius and his family returned to Chicago in 1873, the country was in an economic panic. Junius’ income from the sale of paintings was not enough, so Sara started teaching penmanship. Nonetheless, Junius was gaining respect in the art community. In 1876 he became an Academician (a professional member) of the Chicago Academy of Design, the forerunner of the Art Institute of Chicago.

Junius would usually take summer and fall sketching trips, to, for instance, the Milwaukee shoreline, to paint directly in the presence of nature. Later, in his studio he would develop these sketches and also would construct compositions from imagination and from previous works, as with On the Winooski River, Vt. and Grey Day in the Catskills . In this way, in the sixties and seventies, Junius provided modest-sized oil portraits of localities and idealized pastoral scenes.