Brauer Museum of Art › Permanent Collection › Virtual Exhibitions › In Quest of Beauty: The Life and Times of Junius R. Sloan, 1827-1900 ›

Portraitist

Portraitist

I have just opened here, and the prospects seem tolerably favorable in as much as there is wealth, taste, and a lack of pictures.

Junius to R.R. Spencer from Princeton, May 18, 1856

Life as a Portraitist

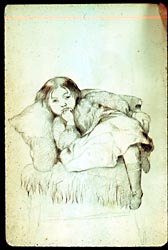

After taking two years off to help his father establish a farm on the Illinois prairie, Junius became resident portraitist in the Bureau County seat, Princeton, Illinois. By 1856 Junius’ portrait production had arrived at the level of finish and workmanship modeled for him by Moses Billings. His drawing was accurate. Head forms were well-defined, with shading and coloring used to create convincing three-dimensional mass. He could offer good commercial portraits, and he got customers.